Date Taken: Fall 2025

Status: Completed

Reference: LSU Professor Daniel Donze, ChatGPT

A critical section is a part of a multi-threaded program that accesses shared resources (like variables or data structures) and must not be executed by more than one thread at a time. This is crucial for preventing race conditions and ensuring data integrity.

A hardware-based synchronization solution uses hardware mechanisms (like atomic instructions or special CPU instructions) to achieve synchronization, while a software-based solution relies on algorithms and data structures (like locks, semaphores, or monitors) implemented in software. Hardware solutions are generally faster but less flexible, whereas software solutions are more versatile but can introduce overhead.

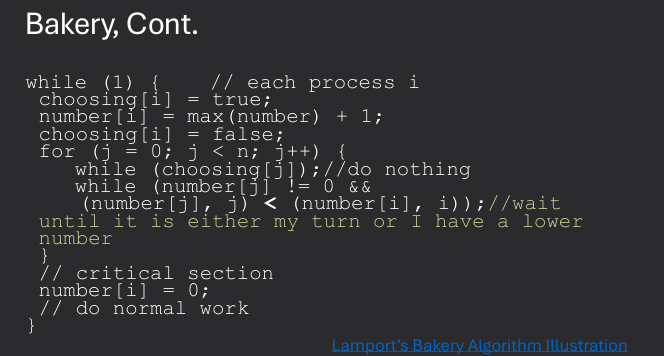

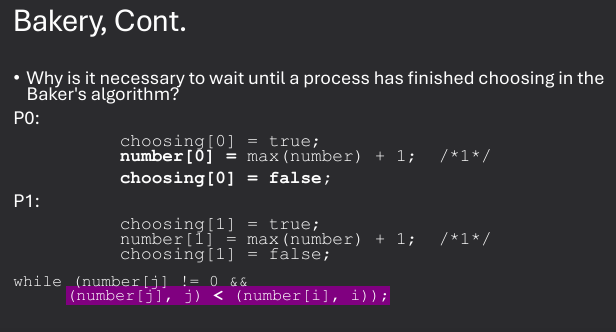

Lamport's Bakery Algorithm is a software-based solution for ensuring mutual exclusion in a distributed system. It assigns a "ticket" to each process that wants to enter its critical section. The process with the lowest ticket number is allowed to enter the critical section. If two processes receive the same ticket number, they are prioritized based on their process IDs. This algorithm ensures that all processes get a fair chance to access the critical section without the need for hardware support.

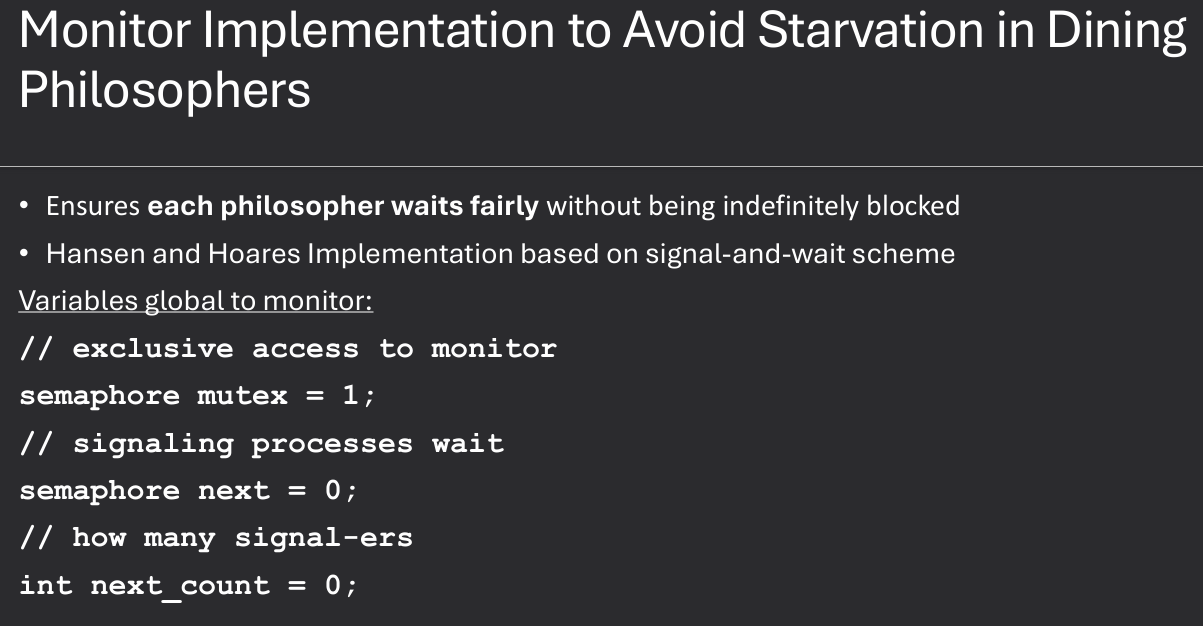

Monitors help solve the Dining Philosophers Problem by encapsulating the shared resources (the forks) and the synchronization logic within a monitor. This ensures that only one philosopher can access the forks at a time, preventing deadlock and starvation. The monitor provides methods for philosophers to pick up and put down forks, ensuring that the necessary conditions for safe access are met.

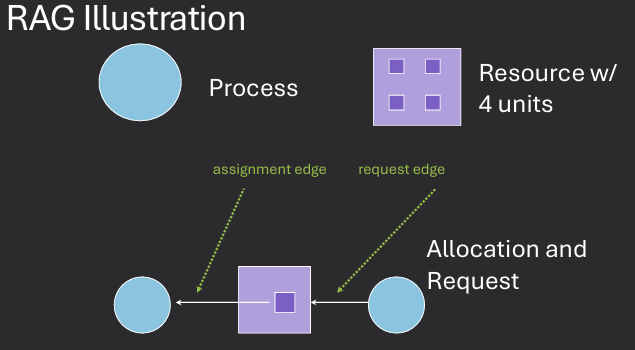

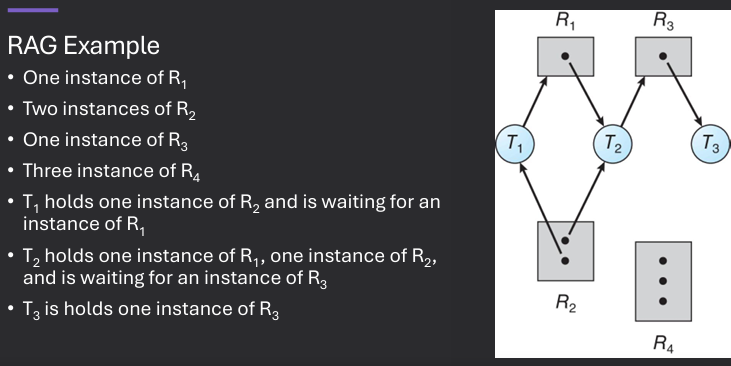

Resource allocation graphs (RAGs) model the allocation of resources to processes in a system. In a RAG, nodes represent processes and resources, while edges represent the relationships between them. Specifically, a request edge from a process to a resource indicates that the process is requesting the resource, and an assignment edge from a resource to a process indicates that the resource has been allocated to the process.

For deadlock to be possible in a resource allocation graph (RAG), the following graph structures must be present:

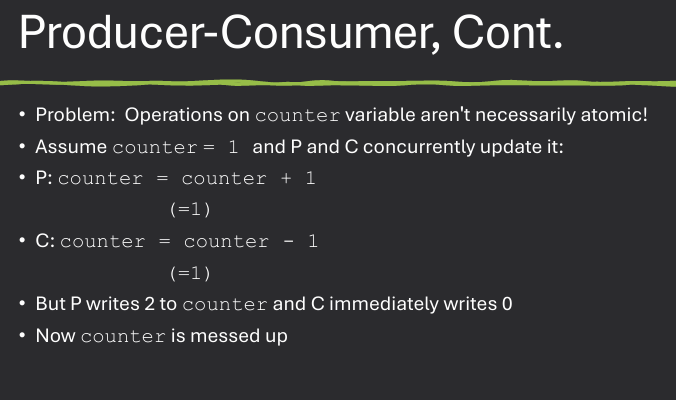

When multiple processes try to update shared data at the same time, the final result may become incorrect due to concurrent (simultaneous) access. For example, consider a int X and the operation X = X + 1; In assembly, this simple statement breaks down into three steps:

(1) Load the value of X from memory,

(2) Add 1 to the value, and

(3) Store the result back to X.

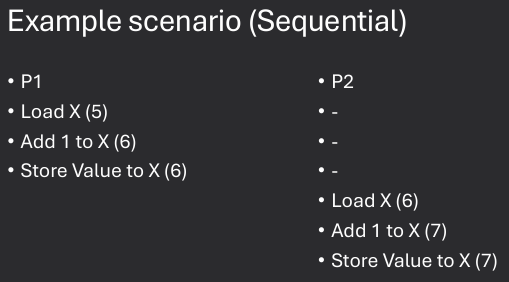

If these operations are executed sequentially (means one after the other) by two processes (P1 and P2), the result will be correct. P1 loads X as 5, adds 1, and stores 6; then P2 loads 6, adds 1, and stores 7, giving a final value of 7.

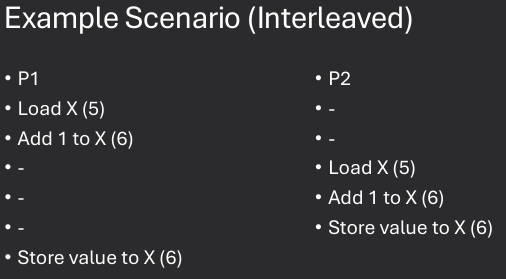

However, if the processes run concurrently (simultaneous) and their steps interleave (overlap in time), both might load the old value (5) before either writes the new one. As a result, both will store 6, and one increment is lost. This situation is called a race condition because the final result depends on which process finishes first. To prevent this, synchronization mechanisms such as locks, semaphores, or atomic operations are used to ensure only one process updates the shared variable at a time.

In this interleaved execution, both processes read the initial value of X (5) before either has written back the incremented value. As a result, both processes compute the new value as 6 and write it back to X, leading to a lost update. The final value of X should have been 7, but due to the race condition, it ends up being 6.

Multiple processes accessing shared data concurrently may lead to incorrect results if not properly coordinated. Thus, we need mechanisms for processes to coordinate data reads and writes. Proper solutions cannot make any timing assumptions, scheduler behavior, or other external factors.

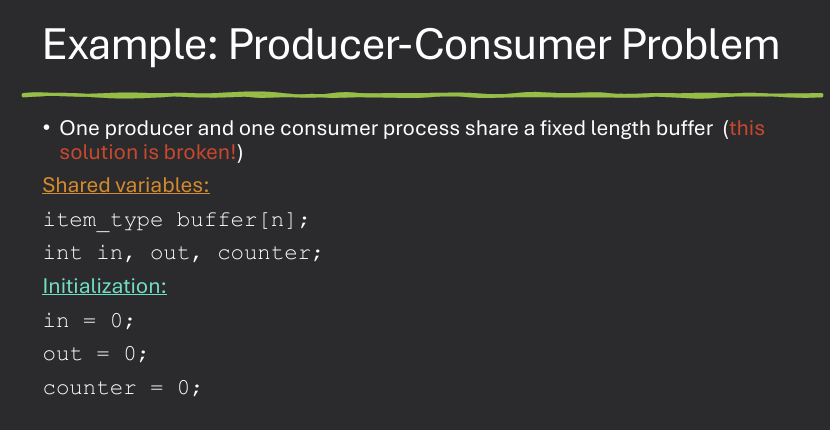

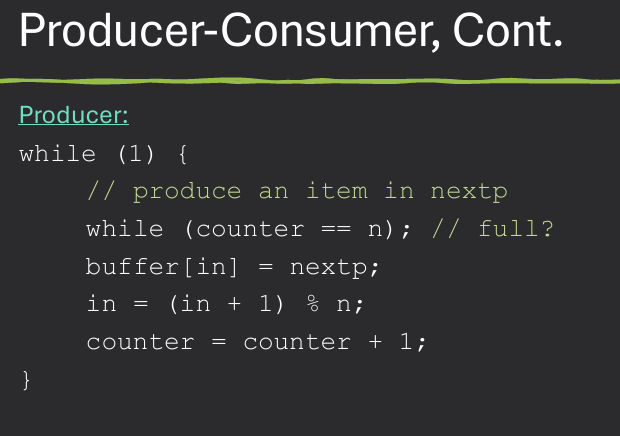

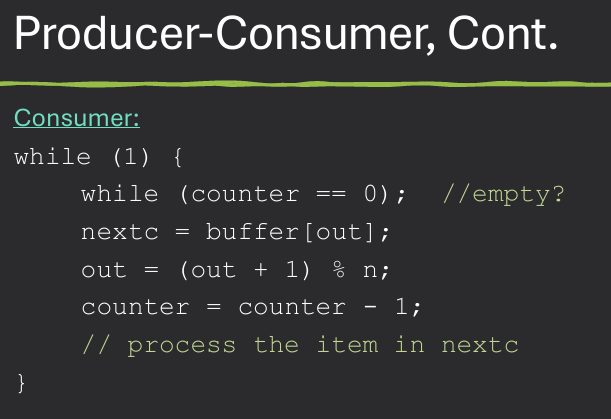

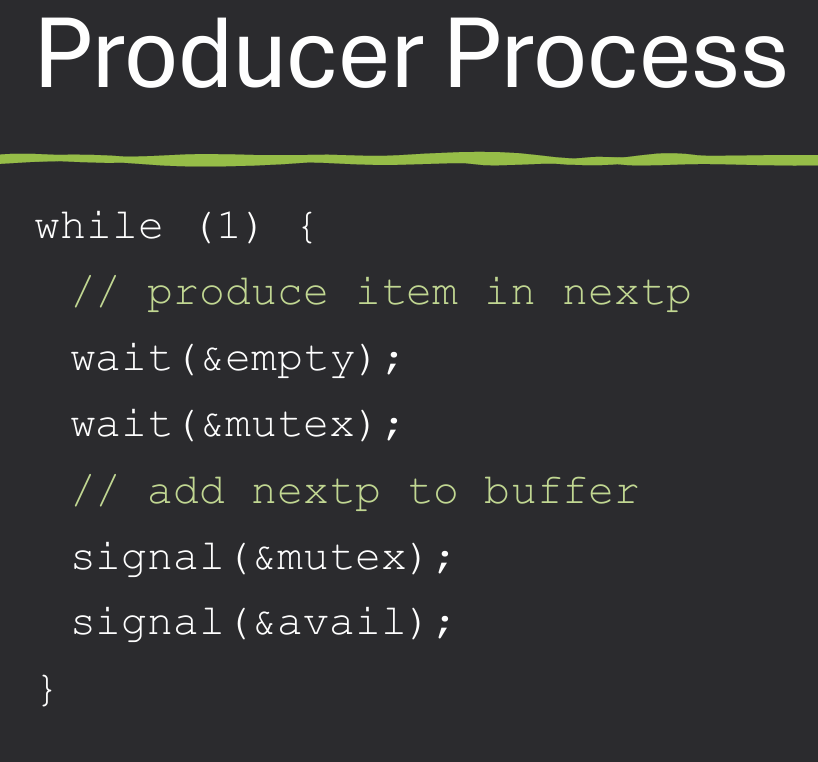

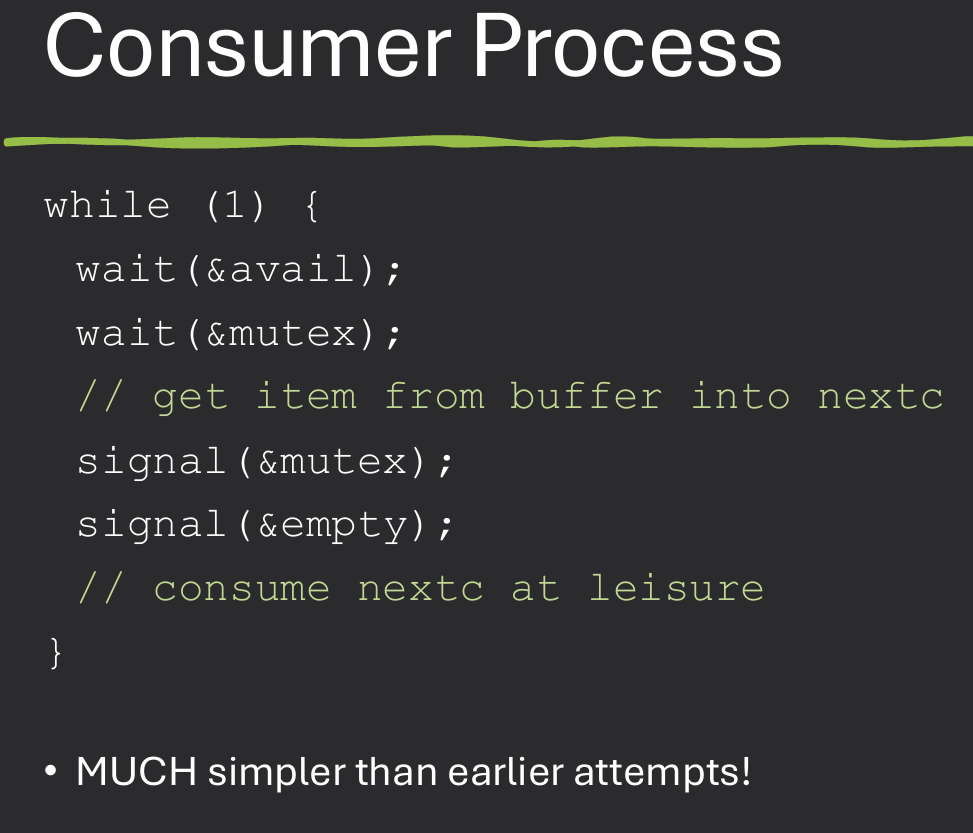

Producer Consumer Problem is a classic example of synchronization issues where producers generate data and place it into a buffer, and consumers take data from the buffer. Proper synchronization ensures that producers do not overwrite data that has not been consumed and consumers do not read data that has not been produced.

A critical section is a part of a multi-threaded program that accesses shared resources (like variables or data structures) and must not be executed by more than one thread at a time. This is crucial for preventing race conditions and ensuring data integrity.

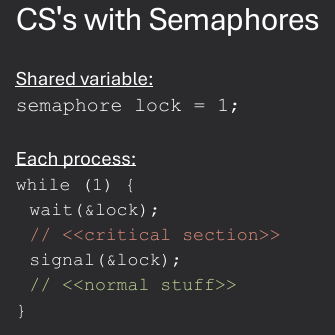

Critical section are the portions of code where a shared resource is accessed or modified. If multiple threads access the critical section at the same time, unexpected behavior or data corruption may occur. Multiple threads, possible multiple critical sections. Synchronization primitives allow processes/threads to limit access to critical sections so that the bad effects are prevented.

Synchronized section are called critical sections. Only one process/thread at a time can access critical section, other must wait. Guarded by atomic operations

Atomic operations are indivisible operations that complete in a single step relative to other threads. This means that once an atomic operation begins, it runs to completion without any possibility of interruption. In short, atomic operations cannot be modified by other threads until the thread performing the operation has completed it.

Atomicity is crucial for maintaining consistency in shared data. If an operation is atomic, it guarantees that no other thread can modify the data being operated on until the operation is complete.

Atomic operations allow for data consistency and prevent race conditions in concurrent (multi-threaded) programming.

Proper solutions to the critical section (CS) problem must satisfy three key properties:

A process must eventually make progress (no infinite loops or blocking calls). No process is allowed to freeze forever.

We cannot assume one process is faster or solwer than another nor assume a process will run before or after another.

We cannot use timing 'sleep()' functions to solve the problem. Waiting based on time does NOT guarantee (one process in CS at a time) multual exclusion.

The algorithm for entering/existing the critical section cannot itself cause race conditions. The lock mechanism must work even if two processes read/write at the same time.

'Process A executes code before any other process could, therefore correct' ← This is wrong because we are NOT allowed to assume any ordering because a process might be preempted (interrupted) at any time. CPU scheduling is unpredictable. No ordering guarantees exist in OS theory. We cannot assume anything about which process runs first or runs more.

Disable interrupts when entering critical section, enable when leaving. Only works in uniprocessor systems. If a process is preempted in its critical section, no other process can run until interrupts are re-enabled. Not suitable for multiprocessor systems as disabling interrupts on one CPU does not affect others.

Entry section: disable interrupts (and preemption). Exit section: enable interrupts.

Will this solve the problem? What if the critical section is code that runs for an hour? Can some processes starve - never enter their critical section? What if there are two CPUs?

Short Answer: Disabling interrupts in the entry section and enabling them in the exit section can solve the race condition problem only on a single CPU system, because it prevents other processes from interrupting during the critical section. However, if the critical section runs for a long time (for example, an hour), other processes will have to wait the entire time and may starve, meaning they never get a chance to run. Also, if there are two or more CPUs, this solution will not work, because disabling interrupts on one CPU does not stop the other CPUs from accessing the shared variable.

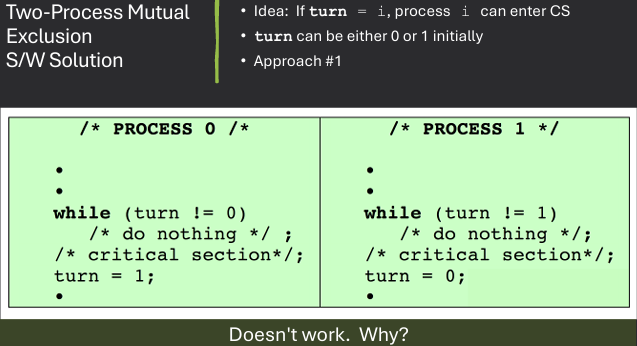

Software solutions for synchronization aim to manage access to shared resources without relying on hardware mechanisms like disabling interrupts. Some common software solutions include:

Process 0

5 runs in the CS

Process 1

2 runs in the CS

Order

P0 → turn = 1

P1 → turn = 0

P0 → turn = 1

P1 → turn = 0 (P1 is now done)

P0 → turn = 1

P0 languishes in purgatory

Criticism of Approach #1:

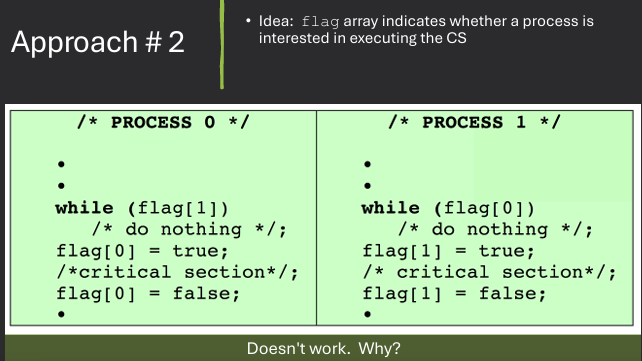

Where #2 falls apart

P0 P1

While(turn[1]) //false off

off While(turn[0]) //false

turn[0] = 1 off

CS off

off turn[1] = 1

off CS

off CS

Criticism of Approach #2:

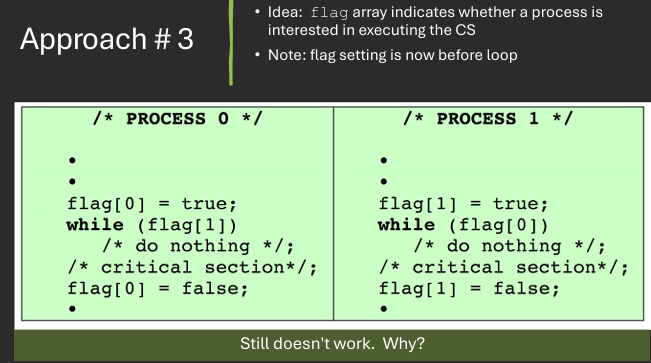

Where #3 falls apart

P0 P1

flag[0] = true; off

off flag[1] = true;

off while(flag[0]); //true

off Nothing

whie(flag[1]); //true off

Nothing off

off while(flag[0]); //true

Criticism of Approach #3:

Dekker's Algorithm is a classic software solution for the critical section problem, designed for two processes. It uses busy waiting and flags to ensure mutual exclusion, progress, and bounded waiting.

The algorithm works as follows:

Dekker's Algorithm ensures that only one process can be in its critical section at a time, and it guarantees that both processes will eventually get a chance to enter their critical sections without starvation.

Peterson's Algorithm is another software solution for the critical section problem, also designed for two processes. It uses two shared variables: an array of flags and a turn variable to ensure mutual exclusion, progress, and bounded waiting.

The algorithm works as follows:

Peterson's Algorithm ensures that only one process can be in its critical section at a time, and it guarantees that both processes will eventually get a chance to enter their critical sections without starvation.

Lamport's Bakery Algorithm is a software solution for the critical section problem that is designed for multiple processes. It is based on the idea of a bakery, where each process takes a number when it wants to enter the critical section, and the process with the lowest number gets to enter.

The algorithm works as follows:

Lamport's Bakery Algorithm ensures that only one process can be in its critical section at a time, and it guarantees that all processes will eventually get a chance to enter their critical sections without starvation.

While software solutions for synchronization are effective, they also have some drawbacks:

Don't want to directly code complex solutions (Bakery algorithm) for every application. Generally can assume atomicity for expressions or assignments to variables of more complex types.

Ex: X = 5; //atomic

X = X + 1; //not atomic

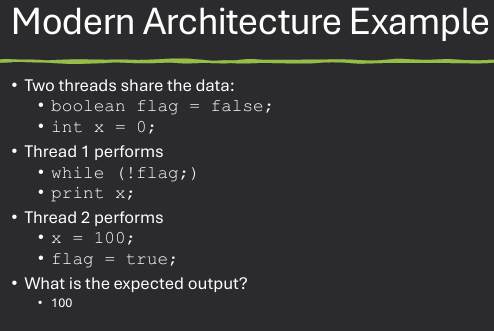

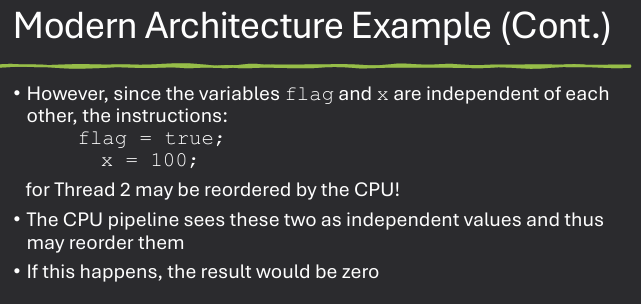

Algorithms such as Peterson's solution is not guaranteed to work on modern architectures. To imporve performance, processors and/or compilers may reorder operations that have no dependencies.

Modern computer architectures often employ techniques like out-of-order execution, speculative execution, and various levels of caching to enhance performance. These optimizations can lead to situations where the order of operations as perceived by one thread may differ from that perceived by another thread, potentially violating the assumptions made by synchronization algorithms like Peterson's solution.

Processors (hardware) may have different memory models. Guarantees it provides to applications.

Strongly Ordered. Changes to memory in one processor are immediately visable in other processors.

Weakly Ordered. Changes to memory in one processor may not be immediately visable in other processors.

Memory fences (also known as memory barriers) are special instructions used in concurrent programming to enforce ordering constraints on memory operations. They ensure that certain memory operations are completed before others are initiated, preventing the compiler or CPU from reordering them in a way that could lead to inconsistencies in multi-threaded environments.

Due to variances in hardware, operating sustems cannot make any assumptions about the memory model used by a systems hardware.

Solution: Memory Fences (Memory Barriers). Hardware instruction ensires all previous load/stores are complete before proceeding. Prevents instruction re-ordering that would interfere with correct results.

Thread 2 now performs

x = 100;

memory_fence();

flag = true;

Now x = 100 must finish before flag = true will start

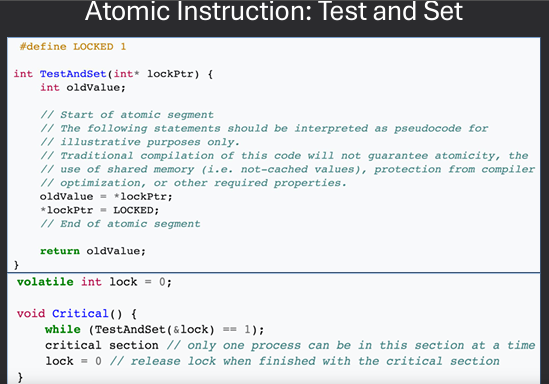

Need hardware support for synchronization to make things easier. No need to guess what's atomic when programming. Two atomic instructions provided by hardware:

Test-and-Set is an atomic instruction that reads a memory location and sets it to a new value in a single operation. It returns the old value, allowing a process to determine if it can enter its critical section.

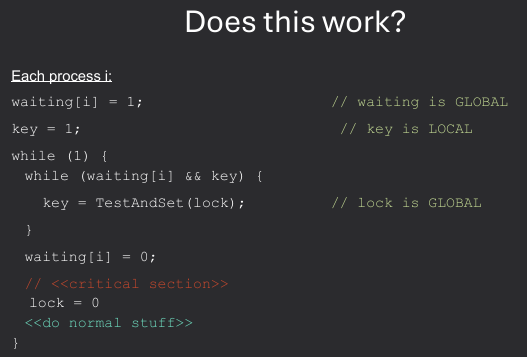

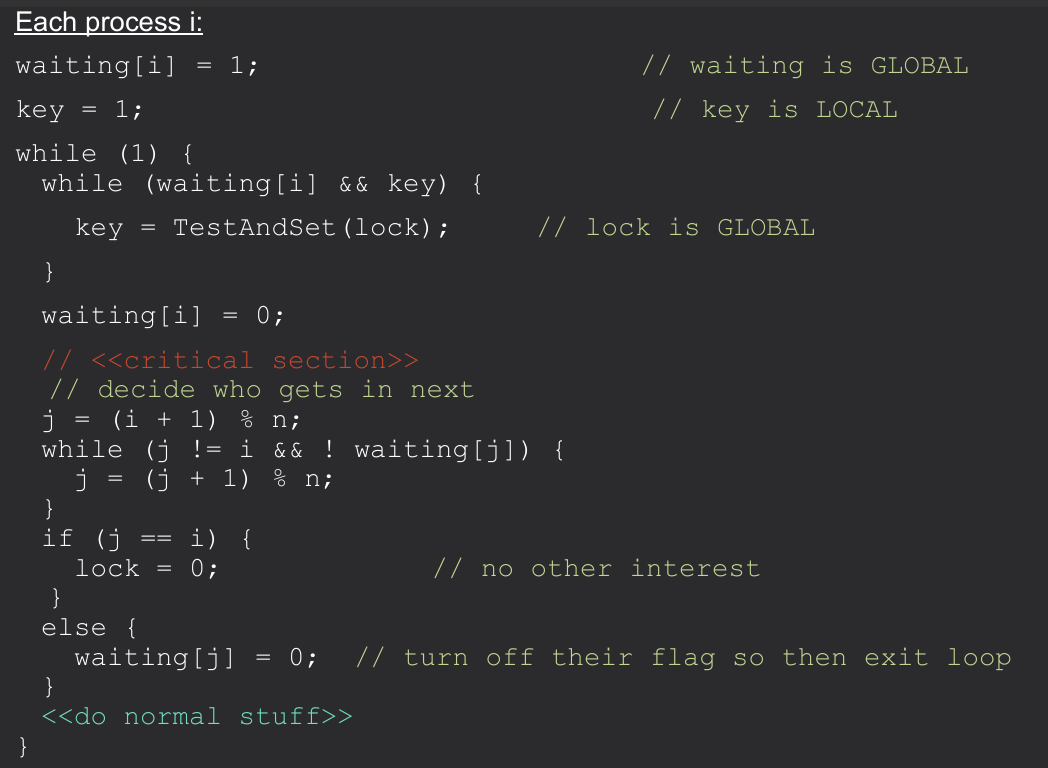

Shared variables/ Initialization:

int lock = 0; //0 = unlocked, 1 = locked

int waiting[n] = {0}; //all n is 0

Local variables / Initialization:

int key, j;

Issue with previous implementation: A particular S process could (theoretically) get beaten to acquiring the lock forever. Thus, it would never get to run. This ciolates the bounded wait principle. Can cause resource starvation.

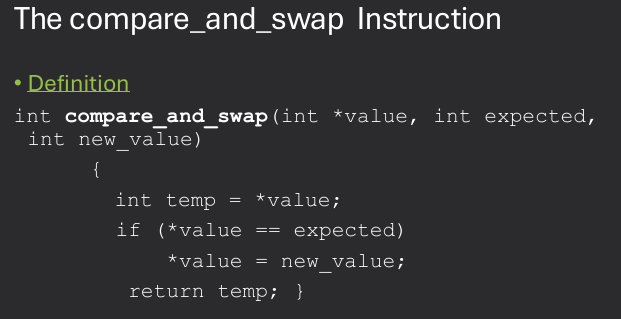

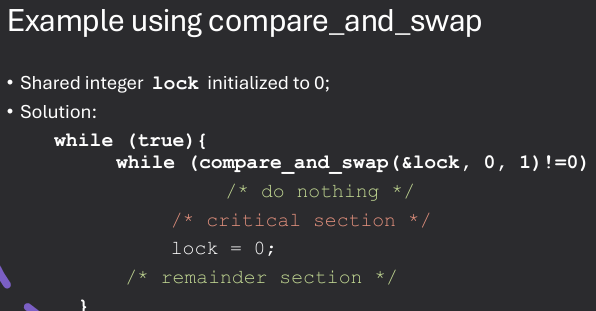

Compare-and-Swap (CAS) is an atomic instruction that compares the contents of a memory location to a given expected value and, if they are equal, swaps it with a new value. This operation is atomic and is often used in lock-free data structures and algorithms.

Execute automatically by hardware. Compares the value at the memory location to the expected value. If they are the same, it updates the memory location to the new value. Otherwise, it does nothing. Returns the original value at the memory location.

Drawback of Hardware Solution. Still very complicated and inaccessible to application programmers. Alternative - OS and programming language support for synchronization: Mutex and Semaphores → software solution

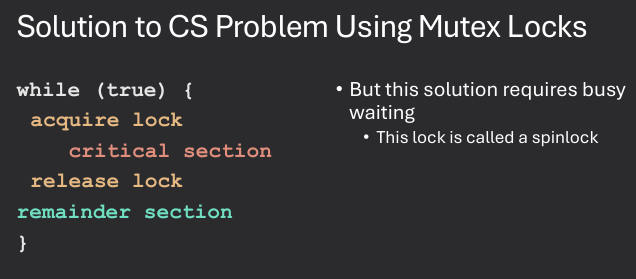

A mutex (short for "mutual exclusion") is a synchronization primitive used to protect shared resources from concurrent access by multiple threads. It ensures that only one thread can access a resource at a time, preventing

Simplest is mutex lock. Boolean variable indicating if lock is available or not.

Protect a critical section by:

First acquire() a lock → perform work in the critical section → then release() the lock

Calls to acquire() and release() must be atomic. Usually implmented via hardware atomic instructions such as compare and swap.

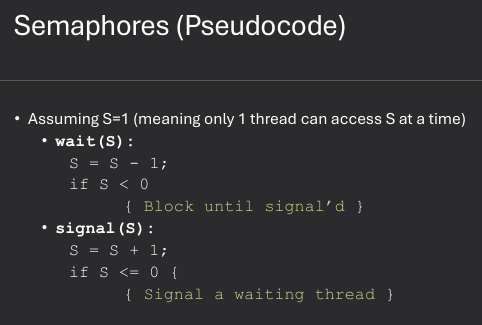

A semaphore is a synchronization primitive that is used to control access to a shared resource by multiple threads. It maintains a count of available resources and allows threads to acquire or release resources in a controlled manner. In short, semaphores allow concurrent processes to run without interfering with each other by only allowing a certain number of processes to access the critical section at the same time and if limit is reached in the critical section, other threads must wait.

The code for the smaphore operations wait() and signal() must be executed atomically. How to do this?

Semaphores are a general purpose synchronization tool. More than just Critical Section. Initialize smaphore sem to 0, then:

P0 P1

- 'Doing Stuff'

- wait(&sem)

P0_func() wait

signal(&sem) wait

- P1_func()

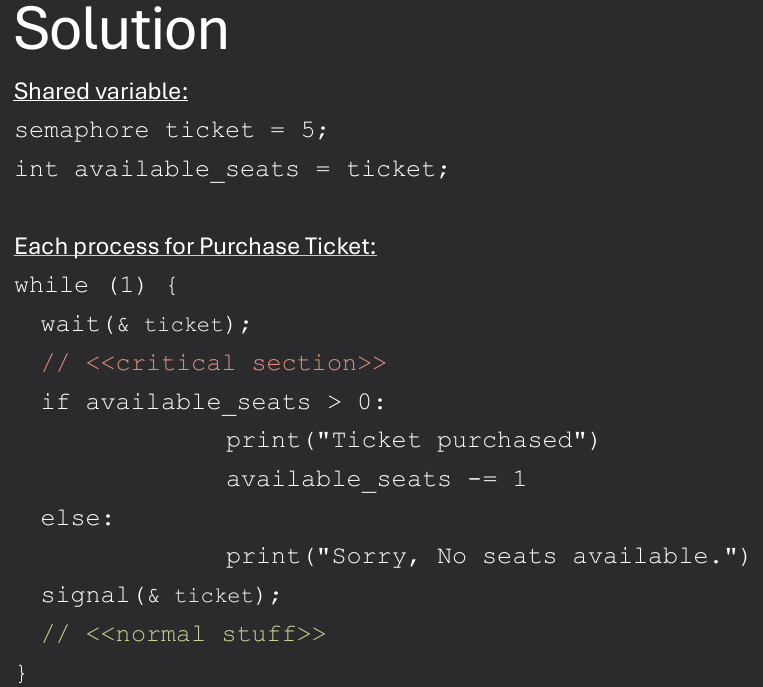

Imagine a live performance at the Ren Fest with a limited number of abailable seats. Multiple spectator (threads) want to purchase tickets, but onlu a 5 seats are open at a time. How can we use semaphores to control access to the available seats?

Chosen because they illustrate the use if synchronization primitives to solve real problems.

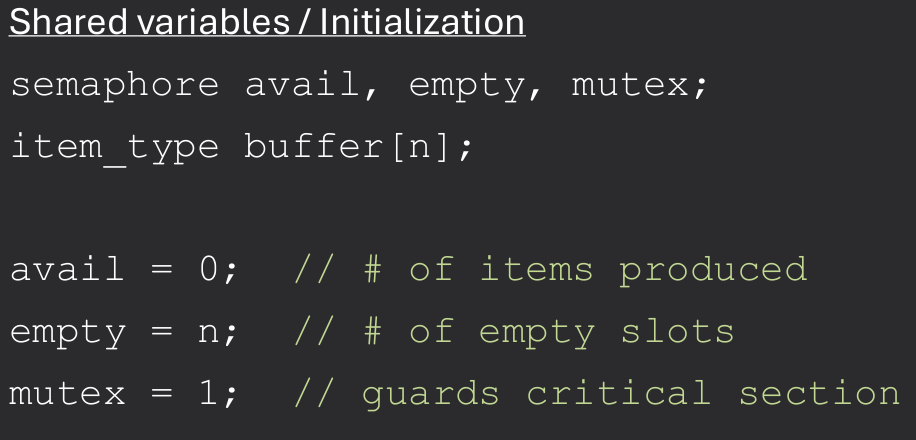

The Bounded Buffer Problem, also known as the Producer-Consumer Problem, is a classic synchronization problem in computer science. It involves two types of processes: producers and consumers, which share a fixed-size buffer (the bounded buffer).

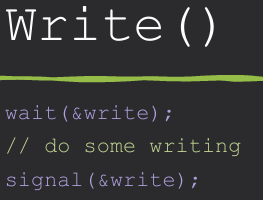

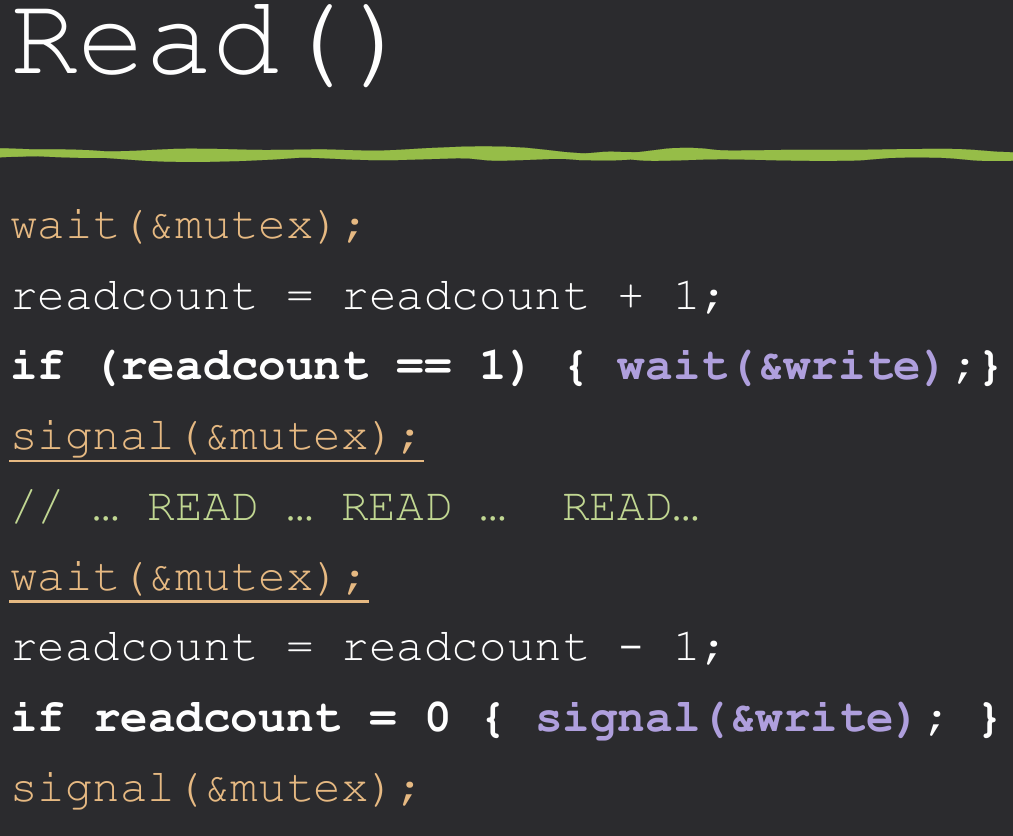

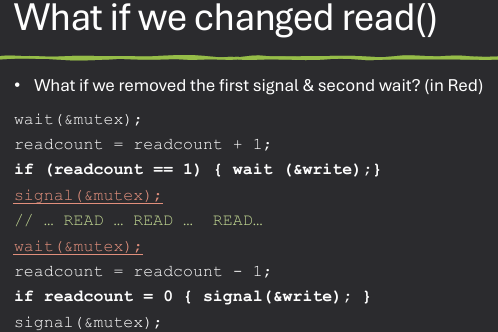

The Readers-Writers Problem is a classic synchronization problem in computer science that involves managing access to a shared resource (like a database) by multiple processes. The challenge is to allow multiple readers to access the resource simultaneously while ensuring that writers have exclusive access when they need to modify the resource.

Shared variables/ Initialization:

semaphore mutex = 1; //for protecting readcount

semaphore write = 1; //for writers

int readcount = 0; //number of active readers

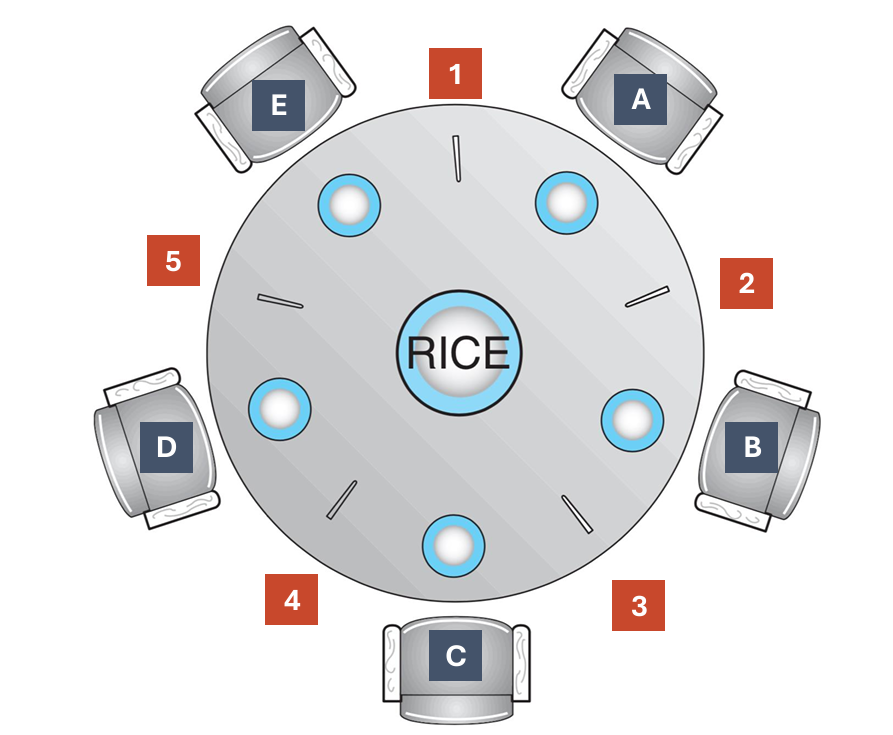

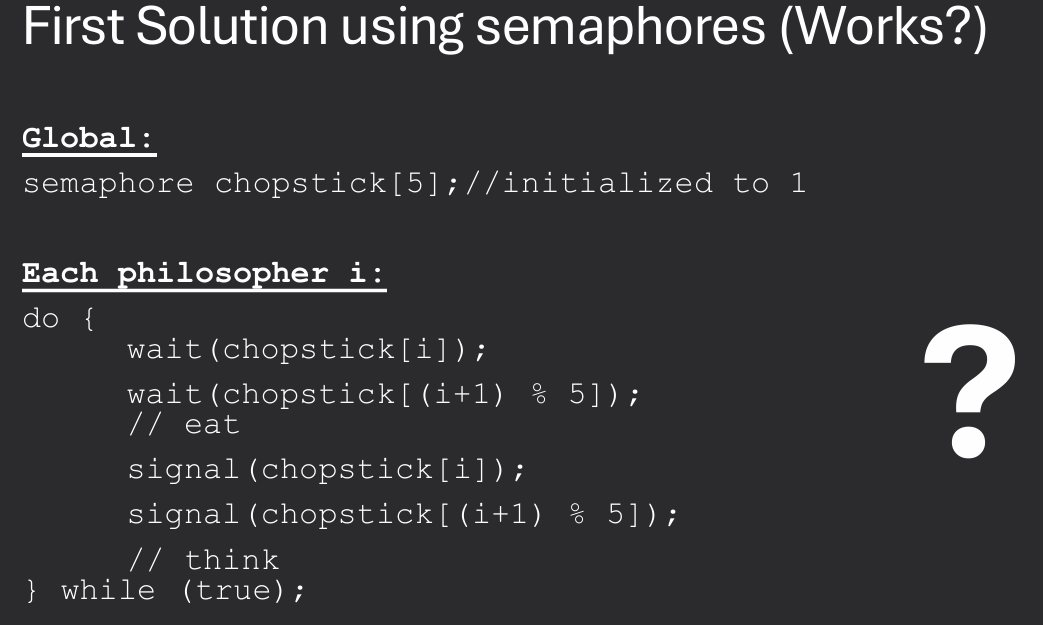

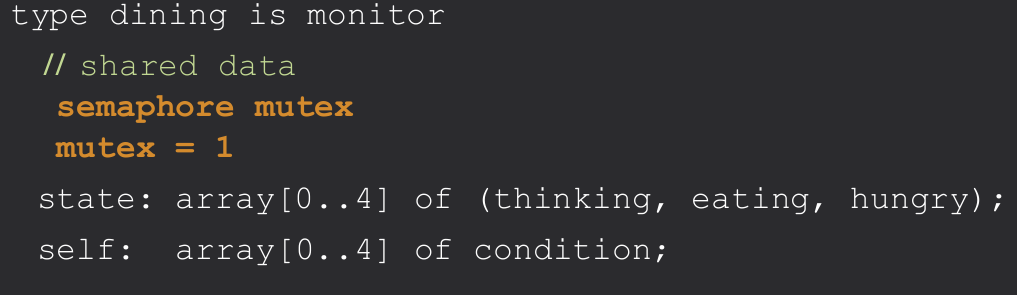

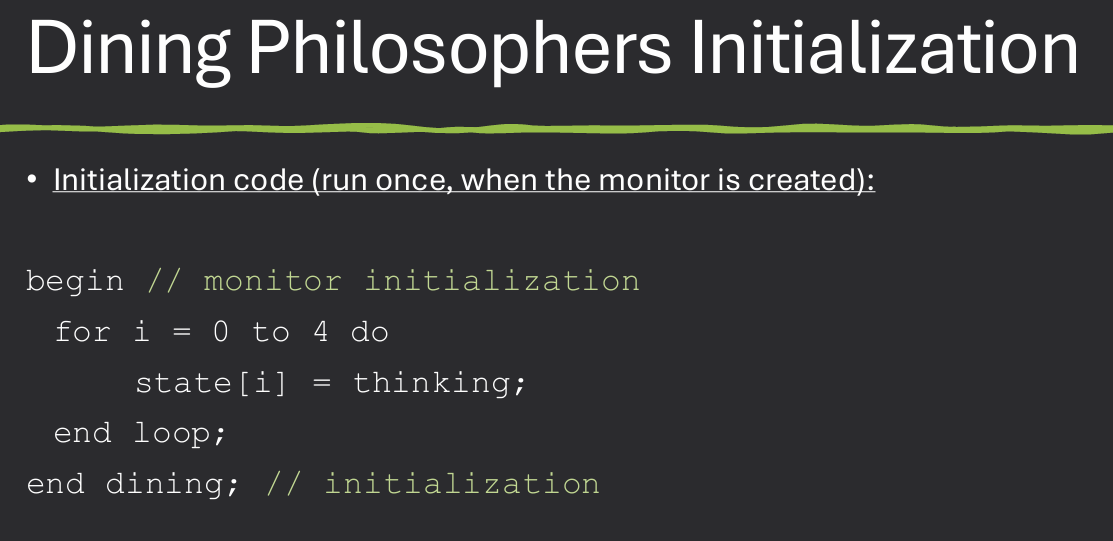

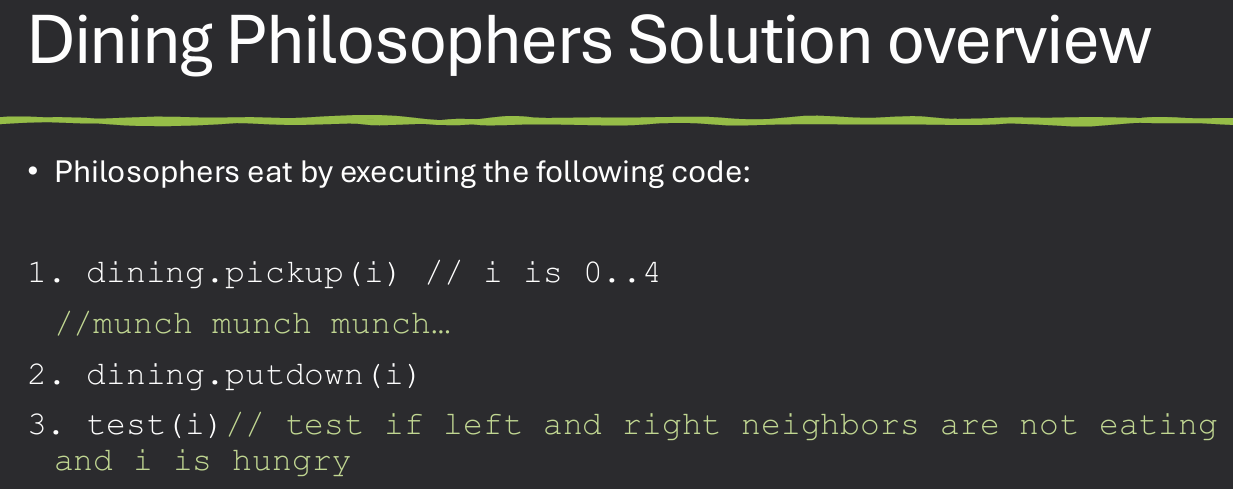

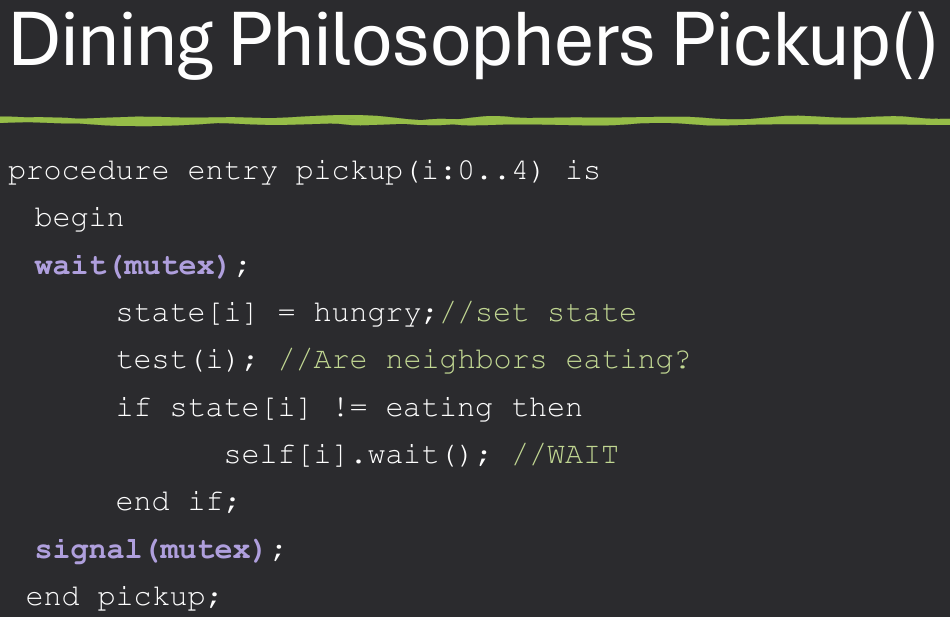

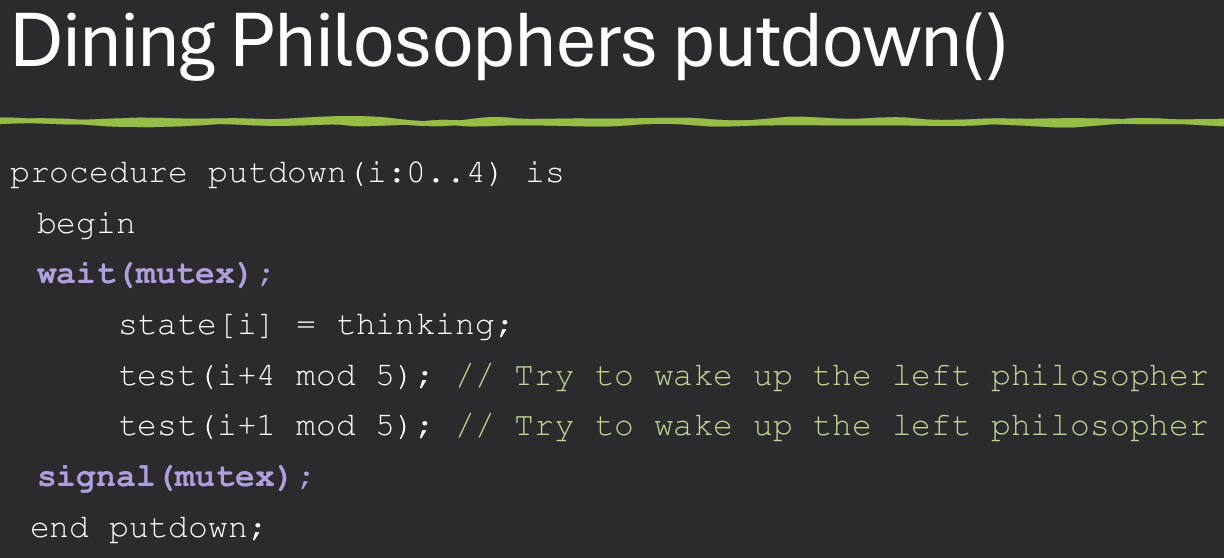

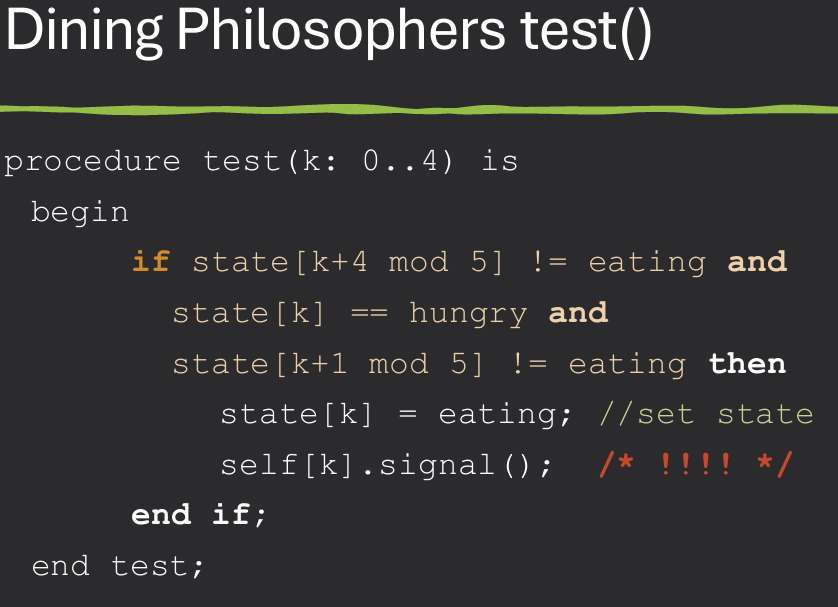

The Dining Philosophers Problem is a classic synchronization problem in computer science that illustrates the challenges of resource sharing among multiple processes. It involves a scenario where a certain number of philosophers are sitting around a table, and each philosopher alternates between thinking and eating. To eat, a philosopher needs two chopsticks, one on their left and one on their right. However, there are only as many forks as there are philosophers, leading to potential deadlock and resource contention.

The best solution to the Dining Philosophers Problem is Monitors

A monitor is a high-level synchronization construct that provides a way to safely manage access to shared resources in concurrent programming. It encapsulates shared data and the procedures that operate on that data, ensuring that only one thread can execute a procedure within the monitor at any given time.

Only one entry procedure is allowed to execute at a time. Means only one thread is active in the monitor at once. This enforced by the implementation automatically

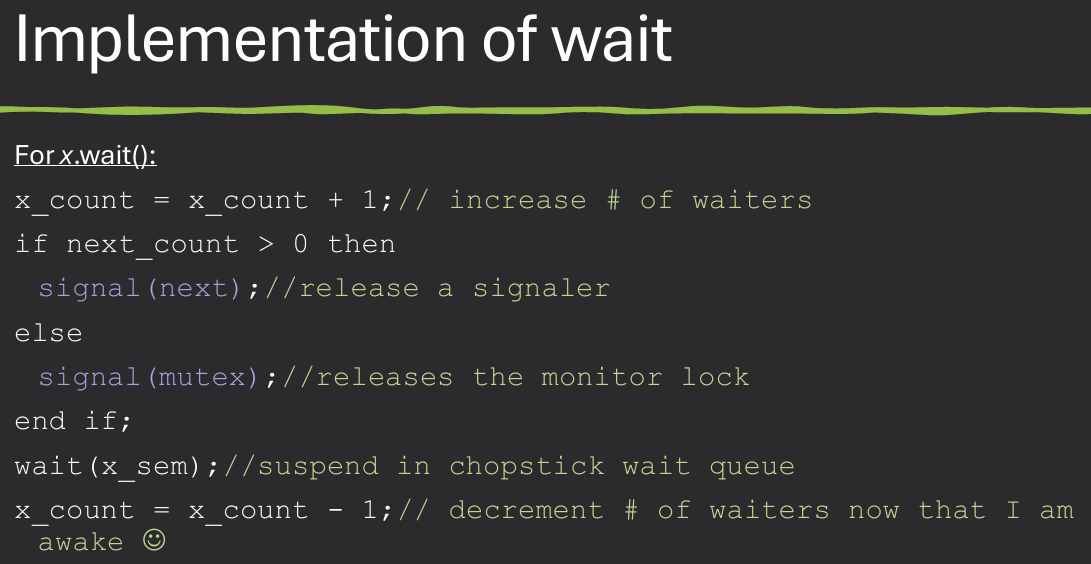

Need to be able to suspend execution temporarily to allow other threads into the monitor using condition variables. Allow threads to wait ot signal each other when certain conditions are met

Condition variables:

x.wait() - put the calling thread to sleep until another thread signals the condition variable

x.signal() - wake up 1 waiting thread (if any)

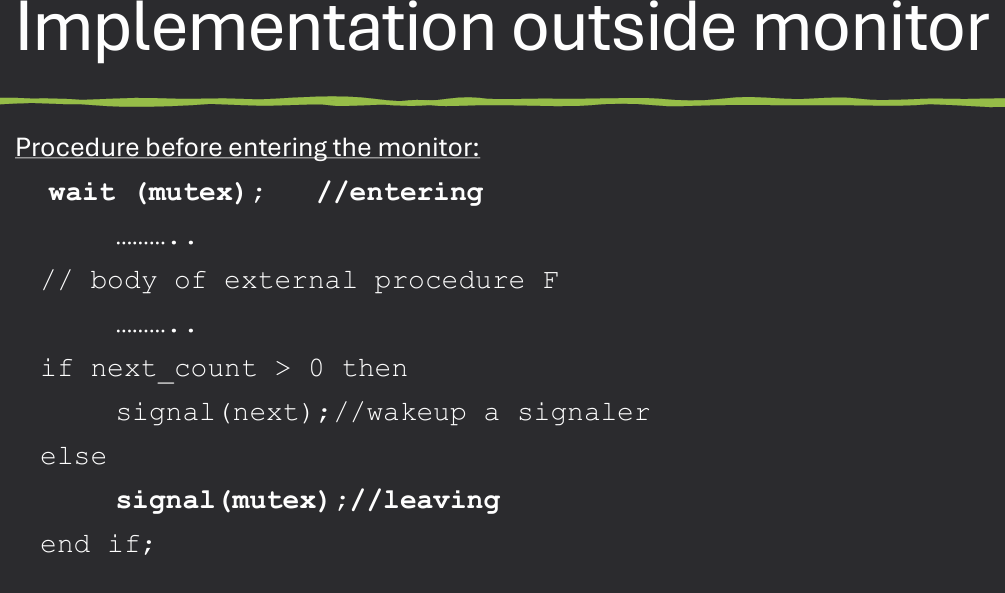

Variables

semaphore mutex

muxtex = 1

Each procedure P is replaced by

wait(mutex);

... body of P ...

signal(mutex);

Mutual exclusion within a monitor is guaranteed

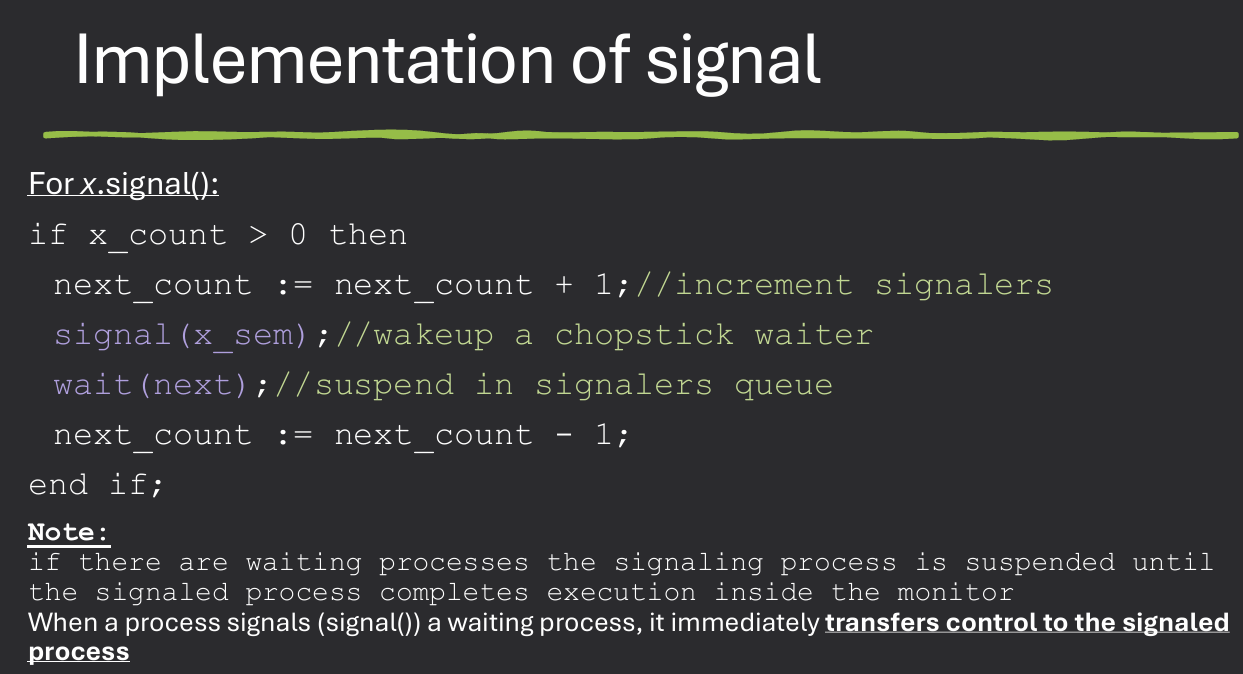

Implementation Initialization: Then every condition variable x needs:

semaphore x_sem = 0;

int x_count = 0;

For monitors to be effective, programs must access shared data via the monitor. Shared data means data that can be accessed by multiple processes/threads. If the resource itself is encapsulated by the monitor, this isn't a problem. Otherwise, requires programming discipline.

Using monitors to solve the Dining Philosophers Problem involves creating a monitor that manages the state of each philosopher and the availability of chopsticks. The monitor ensures that only one philosopher can pick up chopsticks at a time, preventing deadlock and starvation. Solution must satisfy the three properties of synchronization: mutual exclusion, deadlock prevention, and starvation avoidance.

Key process for Monitor implementation: Check if neighbors are eating, if so then wait. If neighbors are NOT eating

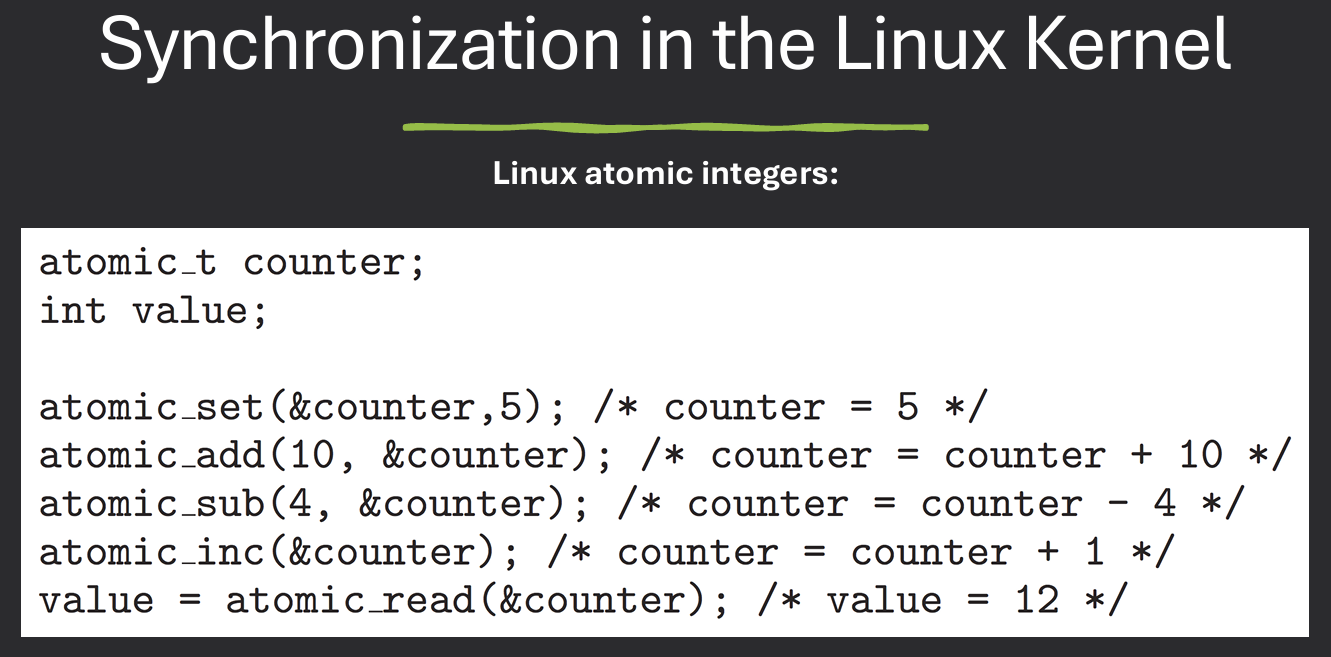

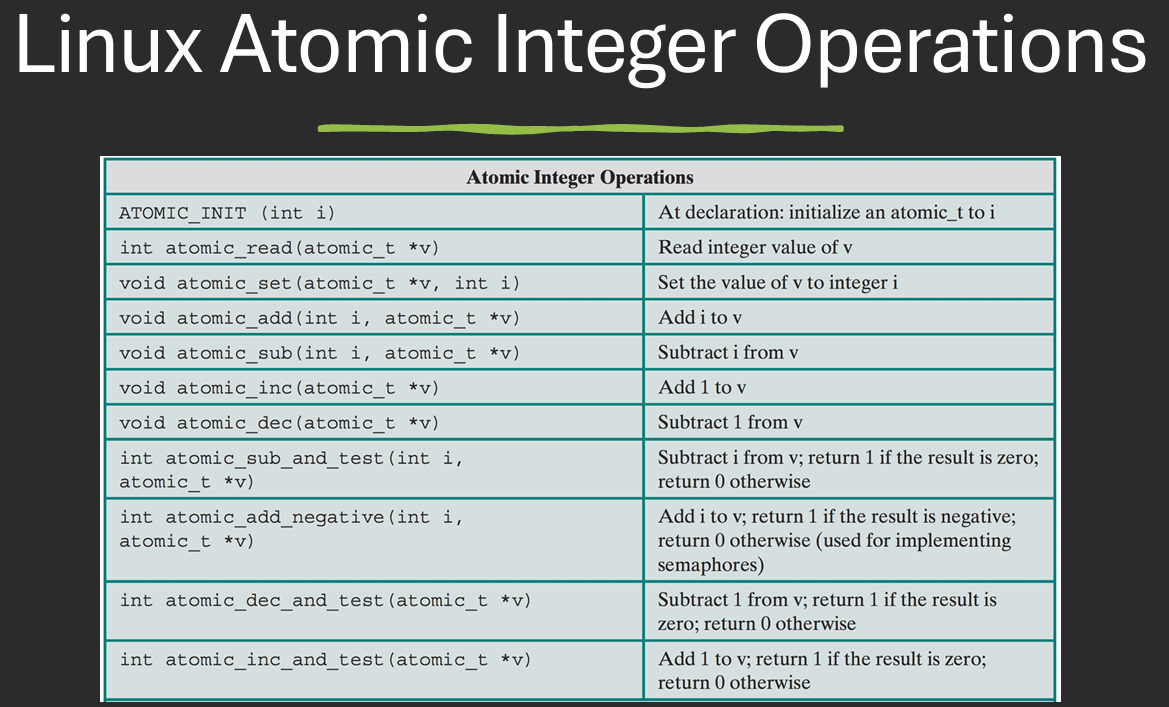

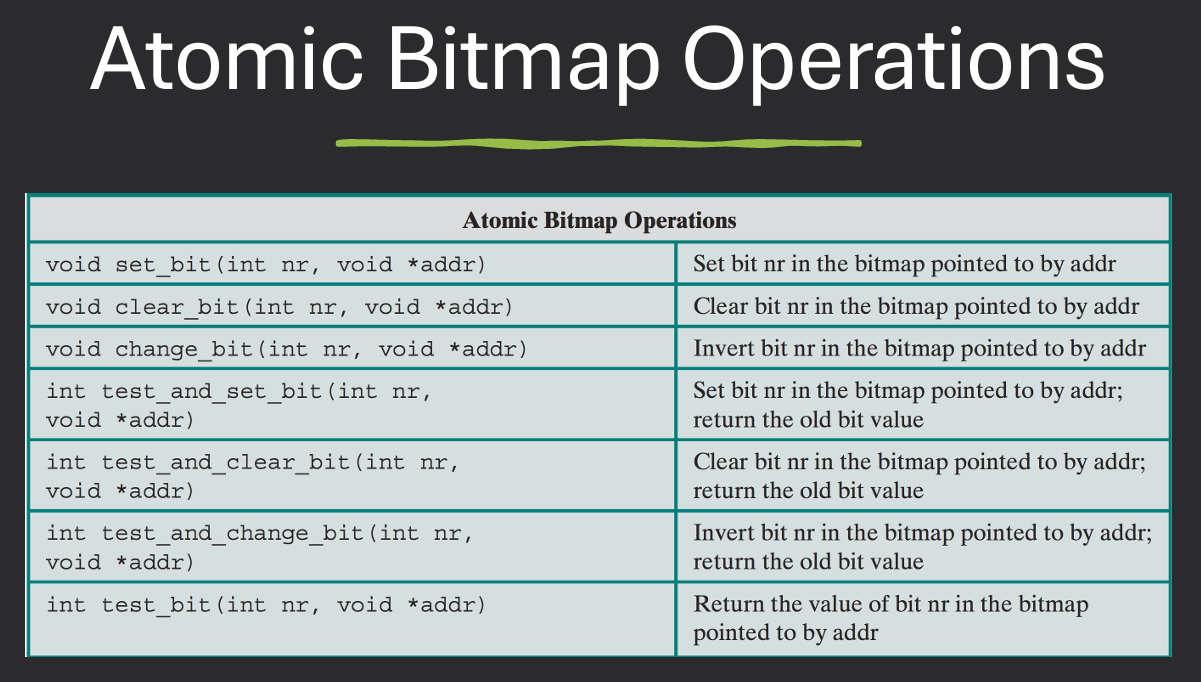

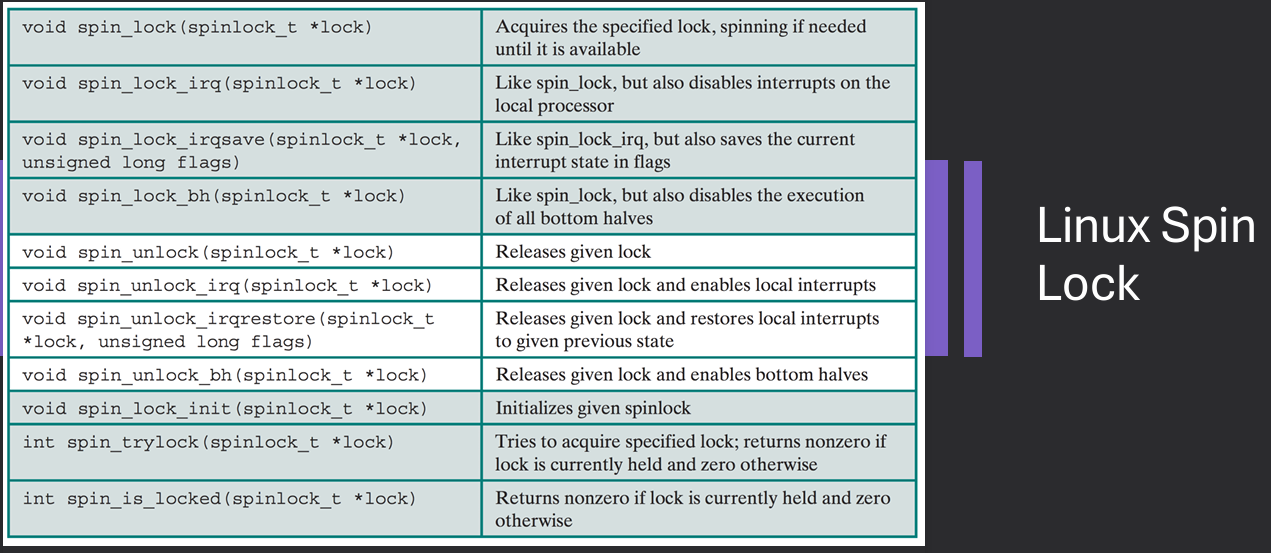

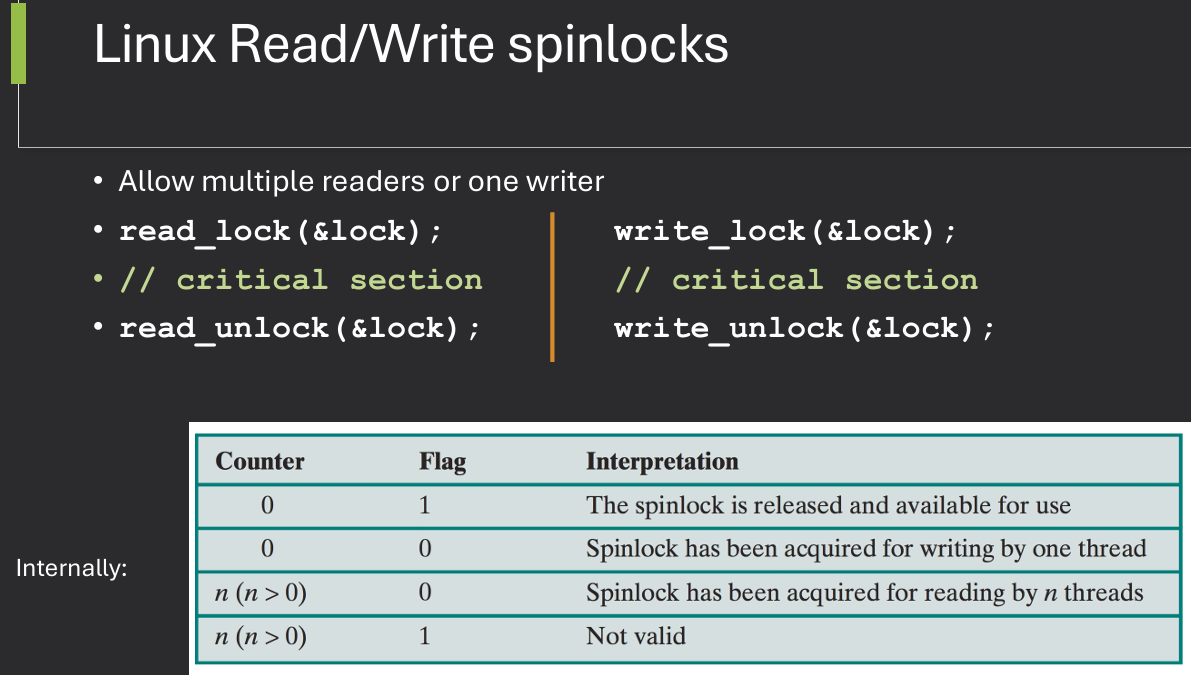

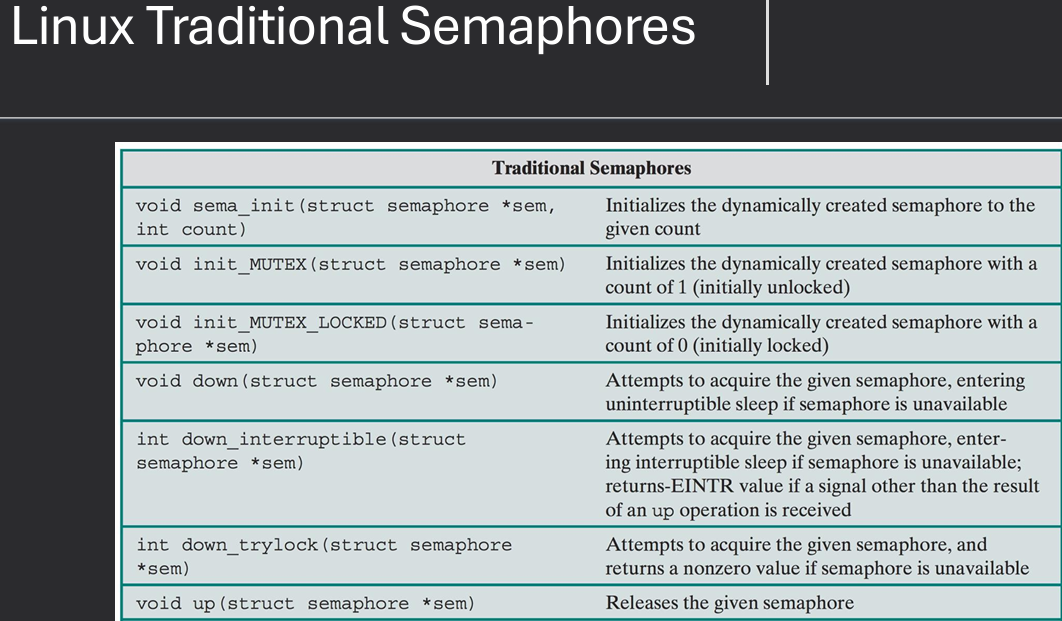

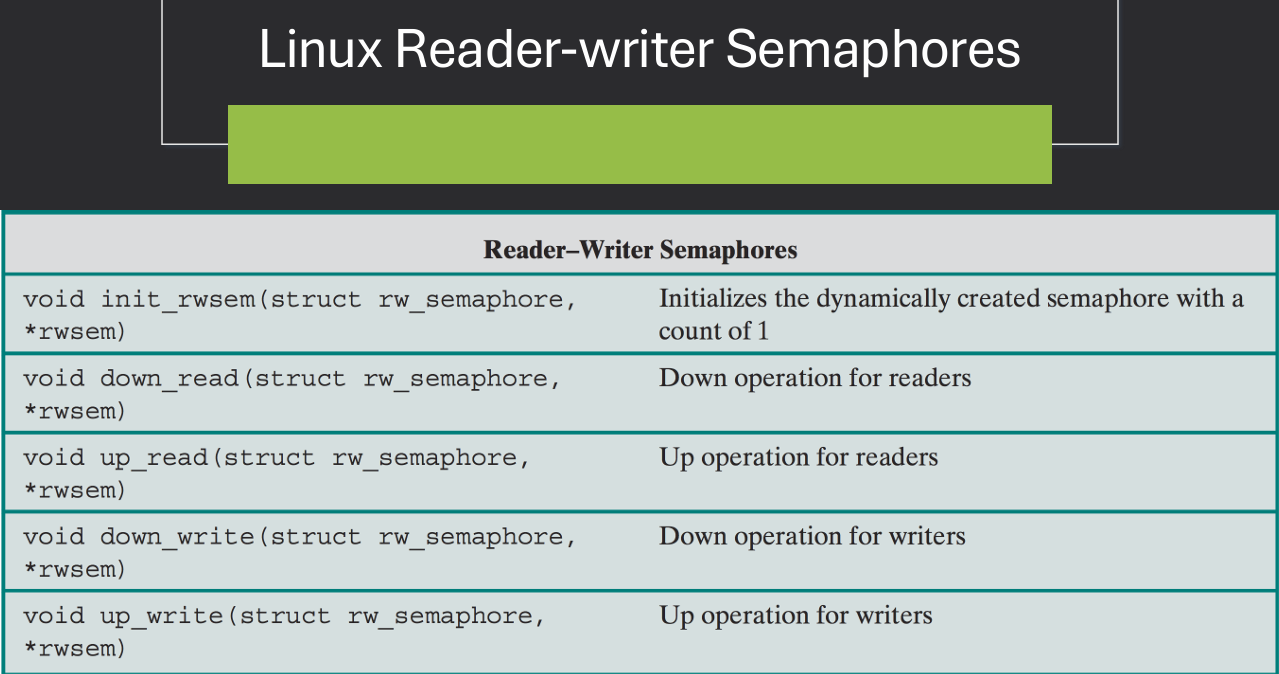

The Linux Synchronization API provides a set of tools and mechanisms for managing concurrency and synchronization in the Linux kernel. It includes various synchronization primitives such as mutexes, semaphores, spinlocks, and read-write locks, which are used to protect shared resources and ensure thread safety.

The Linux kernel employs various synchronization mechanisms to manage access to shared resources and ensure the integrity of data structures in a multi-threaded environment. These mechanisms include mutexes, semaphores, spinlocks, and read-write locks, each serving different purposes based on the context of use.

Linux spinlocks:

spin_lock(&lock);

// critical section

spin_unlock(&lock);

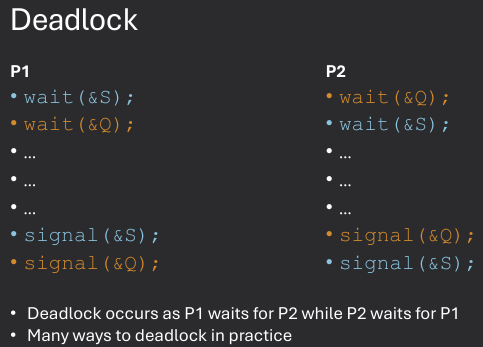

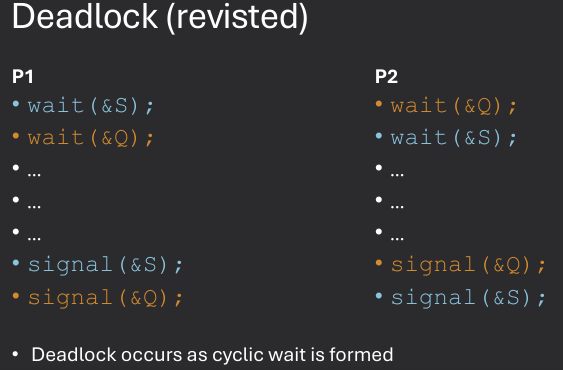

A deadlock is a situation in computer science where two or more processes are unable to proceed because each is waiting for the other to release a resource. This results in a standstill where none of the processes can continue their execution.

Resource types R1, R2, R3, ...

Resource are memory, I/O devices, CPUs, etc. Each resource R_i has W_i instances. Total number of "units" of the resource. Processes use resource as follows: Request resource, Use resource for a finite amount of time, Release resource.

We'll model systems using a resource-allocation graph (RAG), which shows: How many units of each resource are available. Which resources have been granted to which processes. Which processes are requesting which resources

A Resource Allocation Graph (RAG) is a directed graph used to represent the allocation of resources to processes in a computer system. It helps visualize the relationships between processes and resources, making it easier to analyze potential deadlocks and resource contention.

Intuitive deadlock definition: two or more processes are permanently involved in a circular wait for resources (circulary dependent on resources)

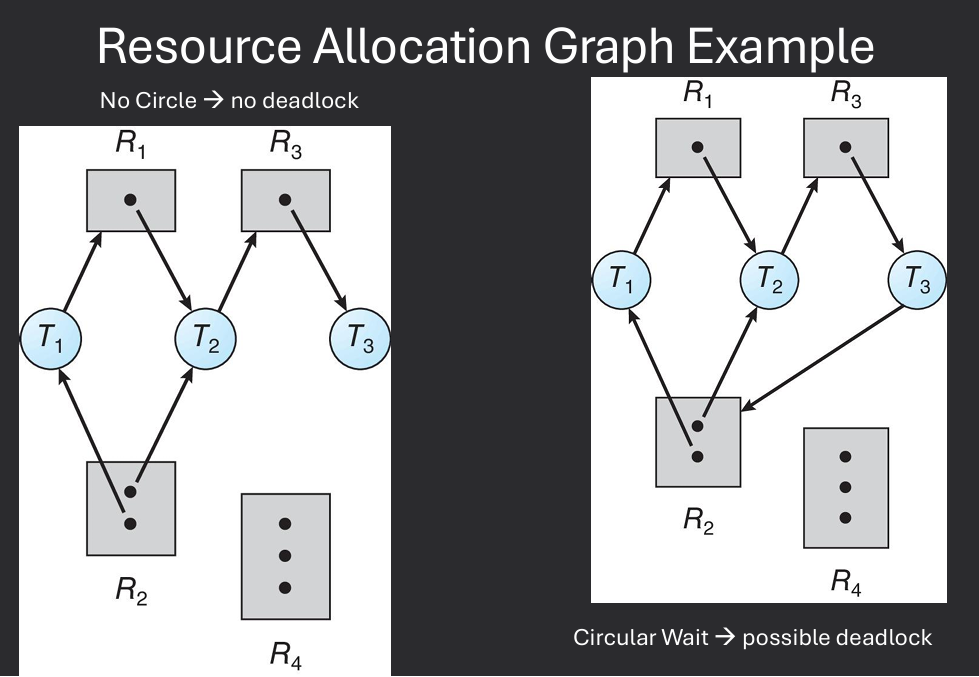

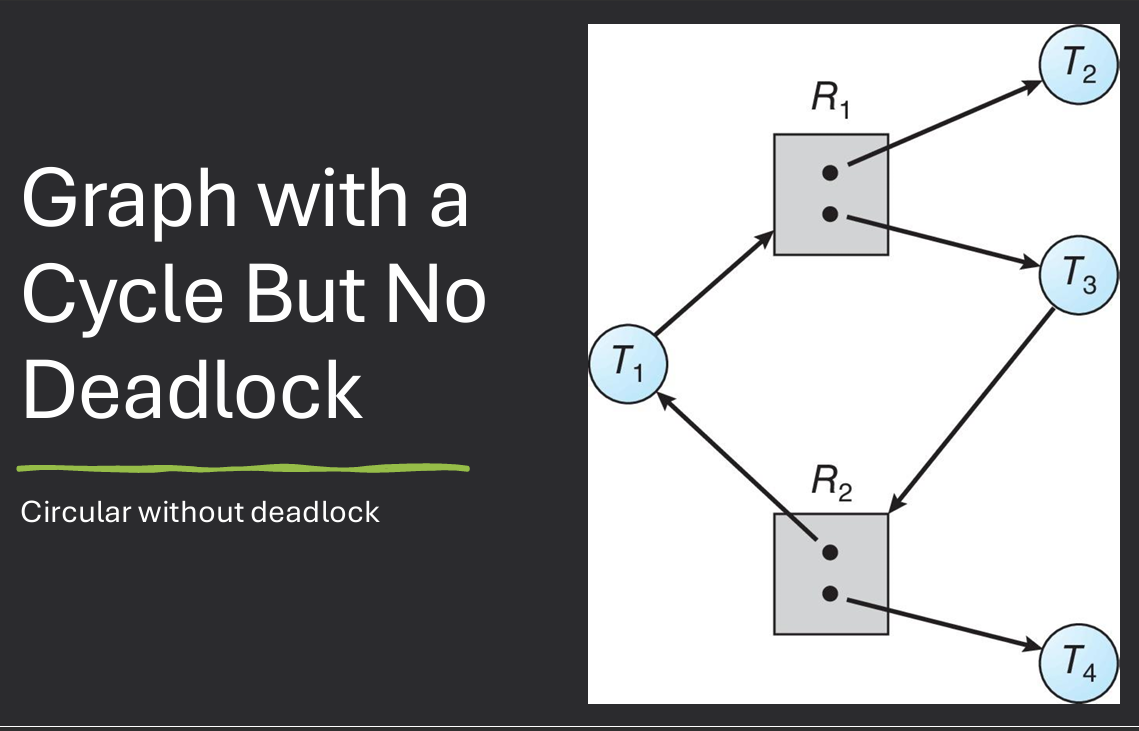

If graph contains no cycles → no deadlock

If graph contains a cycle → deadlock may exist. If only one instance per resource type, then deadlock. If several instances per resource type, possibility of deadlock.

Existence of a circular wait is a necessary but not sufficient condition for deadlock.

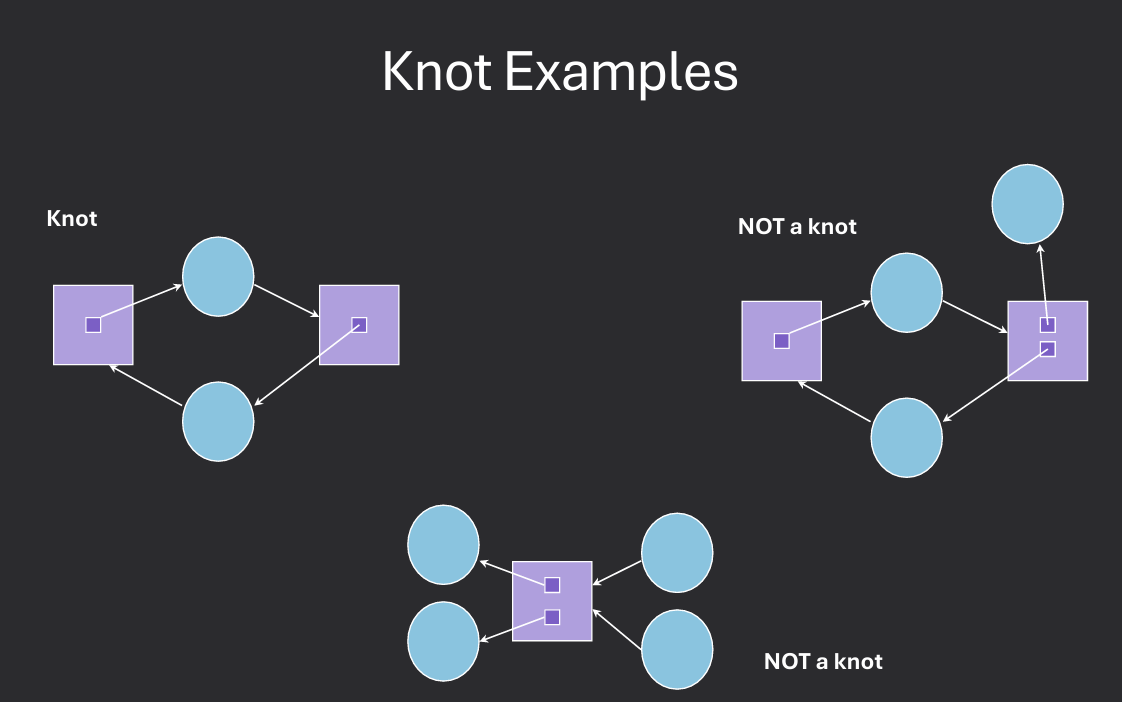

A strongly connected subgraph of a directed graph, such that starting from any node in the subgragh it is impossible to leave the subgraph by following the edges of the graph

Simplest method for handling deadlock: Don't. Pretend deadlock will never happen. Or assume that if it does happen the system will exhibit "strange" behavior. At which time it can be rebooted.

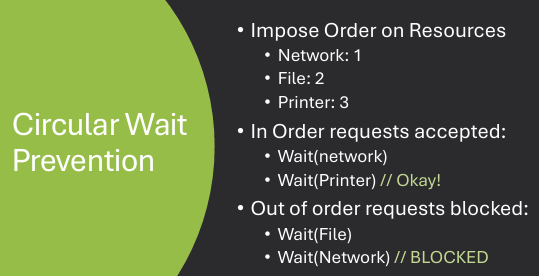

Prevent at least one of the four necessary conditions to occur, thus making deadlock impossible. To prevent deadlock:

Deadlock avoidance requires that the OS have additional information about how resources are to be requested. With this information, the OS can decide whether a particular resource request can be granted immediately or must be delayed to avoid a possible deadlock situation.

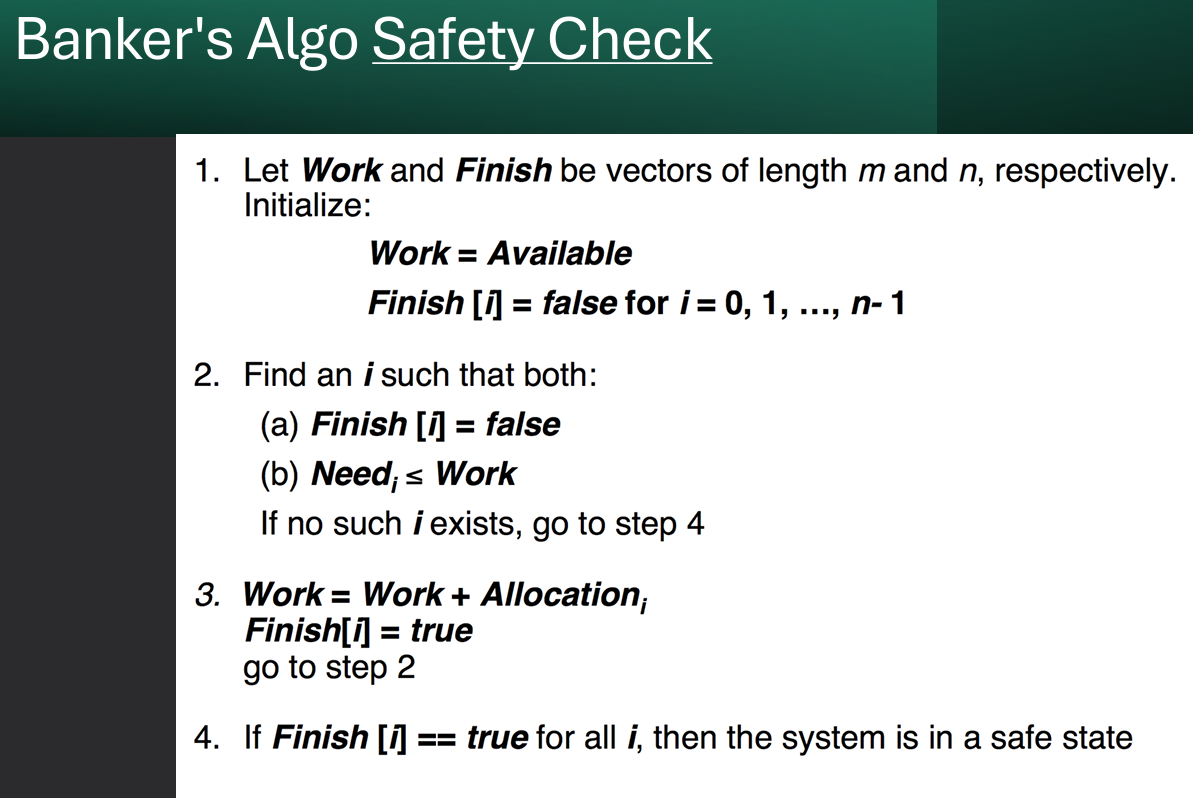

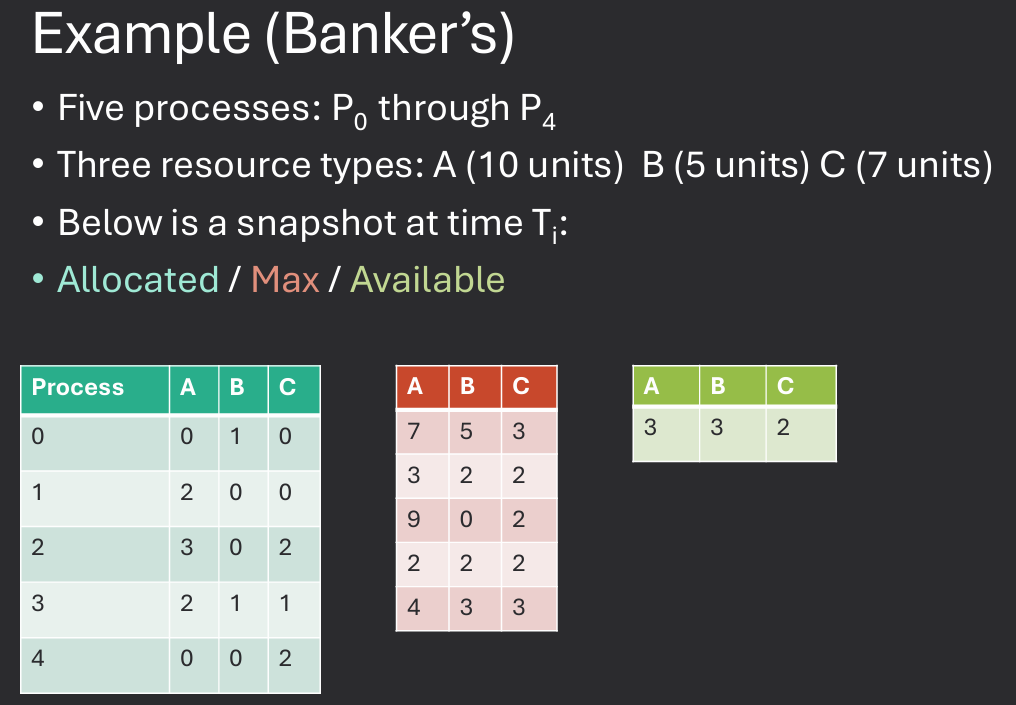

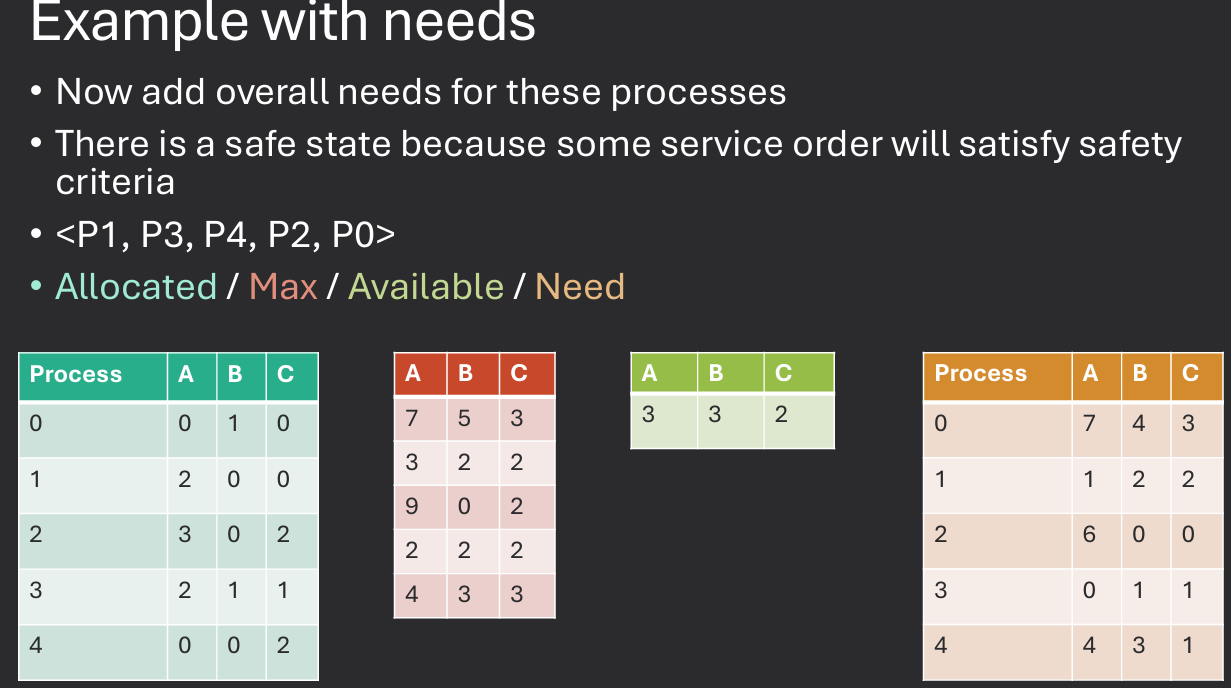

"Unsafe" means possibility of deadlock, not necessarily deadlock. Banker's Algorithm used to keep system in a safe state. Named because in a banking situation the algoritm might be used to ensure that the bank never e=overextended itself financially (with $$ as resource). Used by OS's in the 1960's for deadlock aviodance.

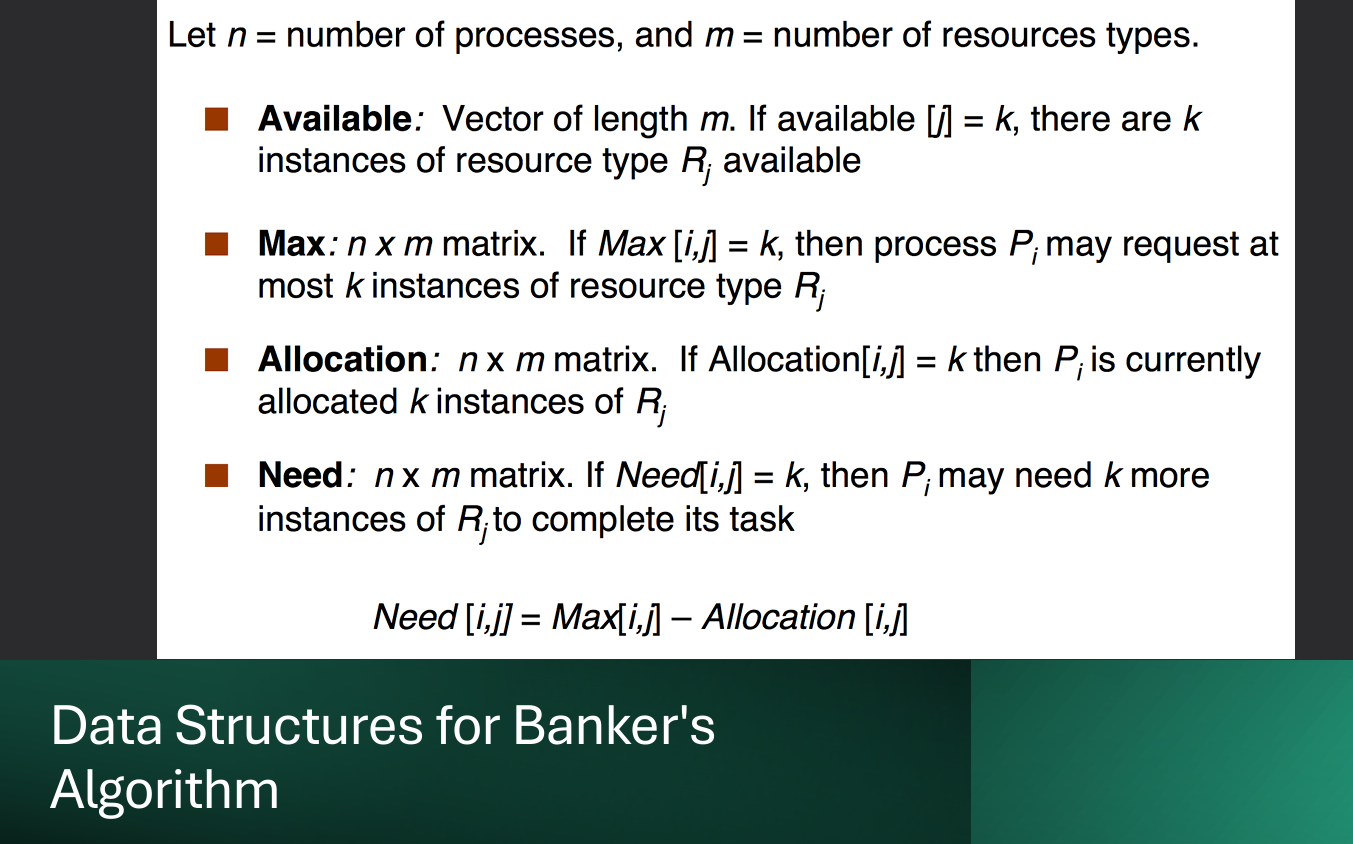

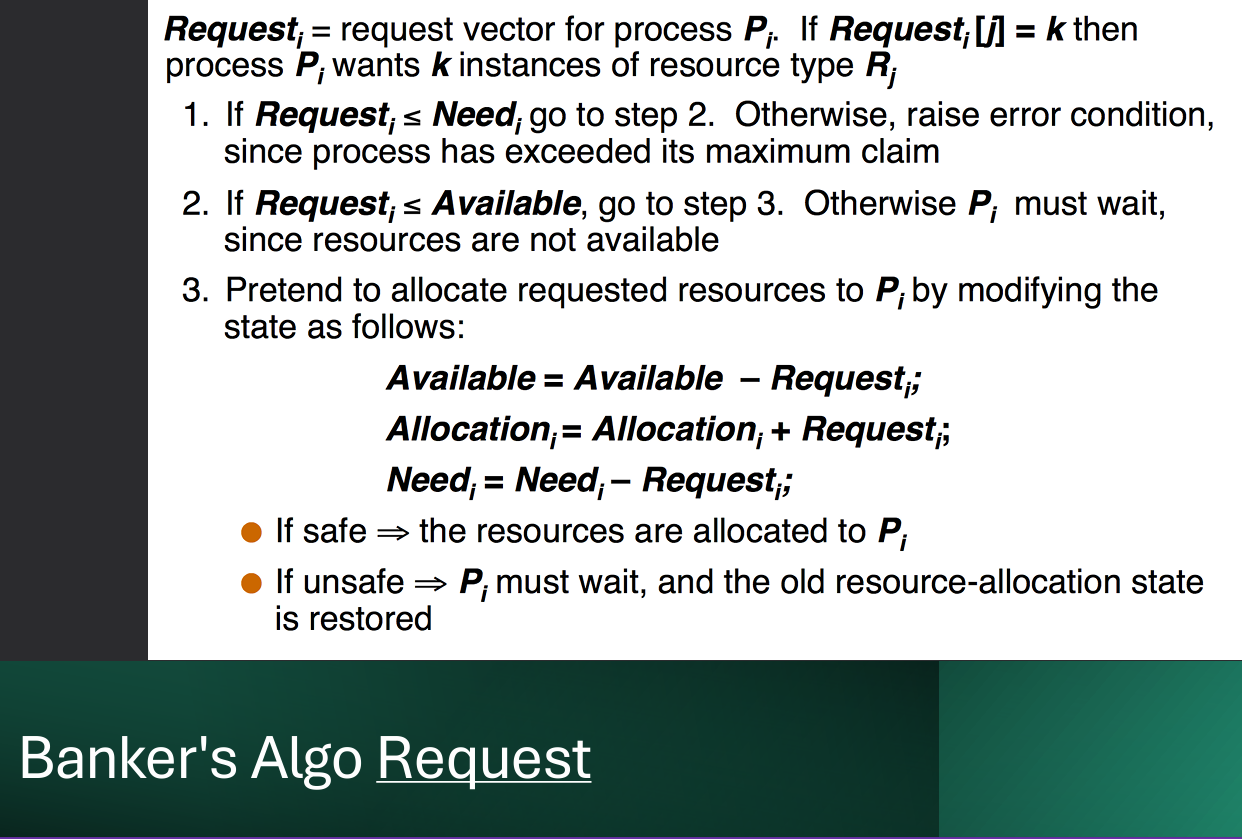

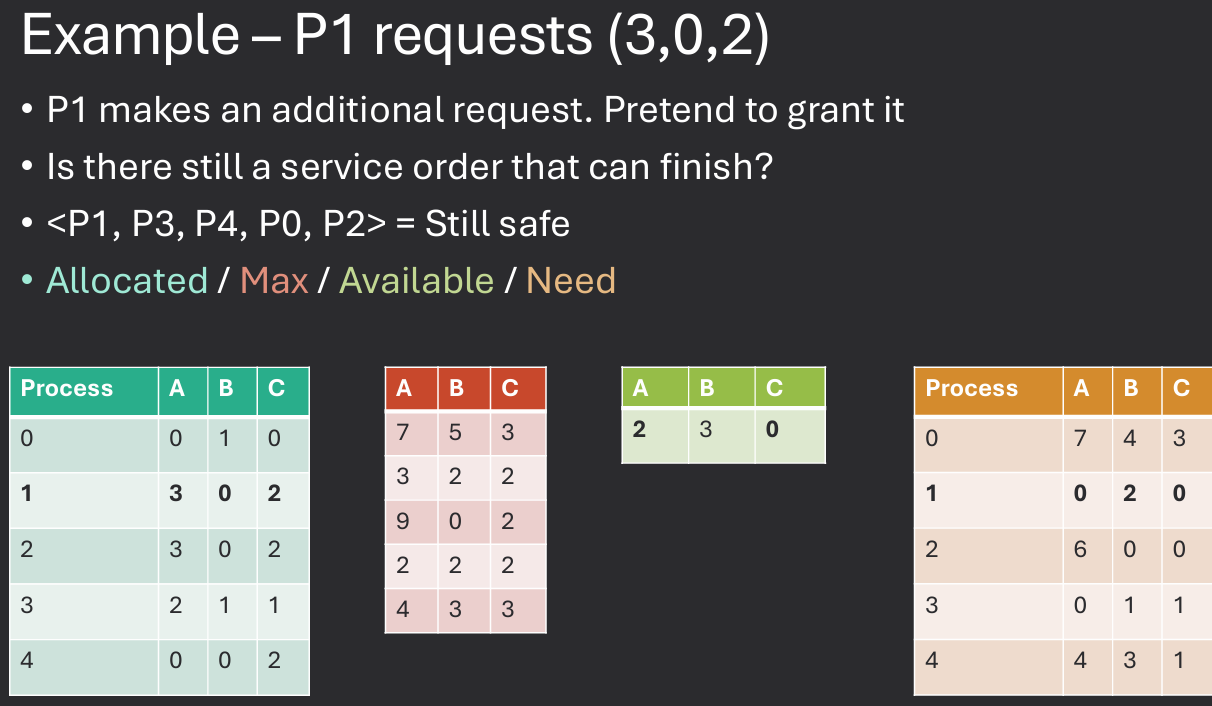

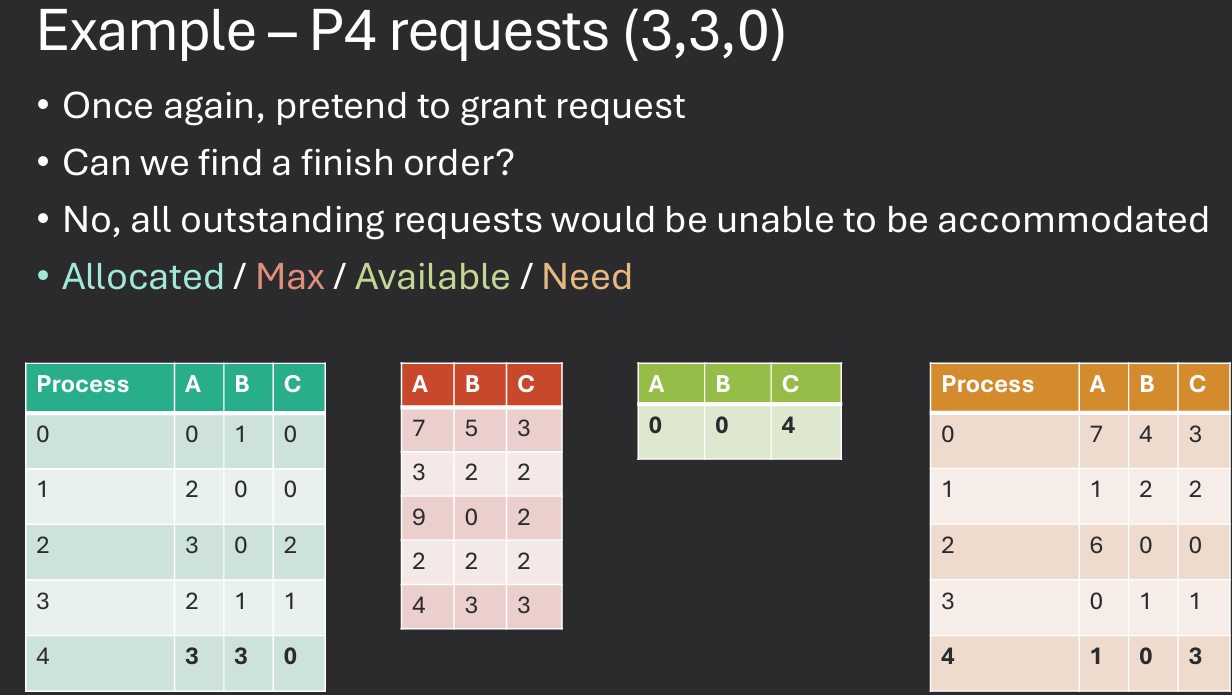

The Banker's Algorithm is a deadlock avoidance algorithm that ensures a system remains in a safe state by carefully allocating resources to processes. It simulates the allocation of resources and checks if the system can still satisfy the maximum resource demands of all processes without leading to a deadlock.

Processes must declare their maximal resource needs. When a process makes a request, the Banker's algorithm determines whether satisfying the request would cause the system to enter an unsafe state. If so, request denied. If not, request granted.

Idea: know the max # of resource units that a particular process may request. Know current allocation for each process and current "need", max - current allocation. When a request is issued,"pretend" to honor the request. Then, assume that process will not relinquish resource until done. Try to fulfill the :needs" (max - current allocation) of all processes in some order. If impossible, deny request

Deadlock detection and recovery involves periodically checking the system for deadlocks and taking action to resolve them when they are detected. This approach allows the system to operate normally most of the time, only intervening when a deadlock situation arises.

For deadlock detection, must provide: Deadlock detection algorithm and Mechanism for getting rid of deadlock.

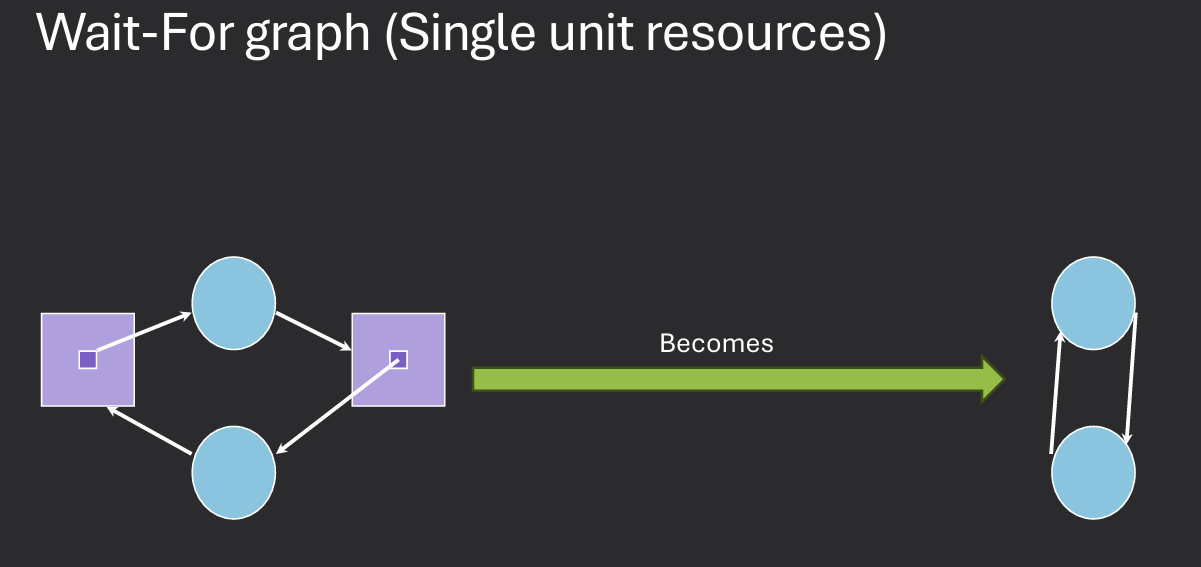

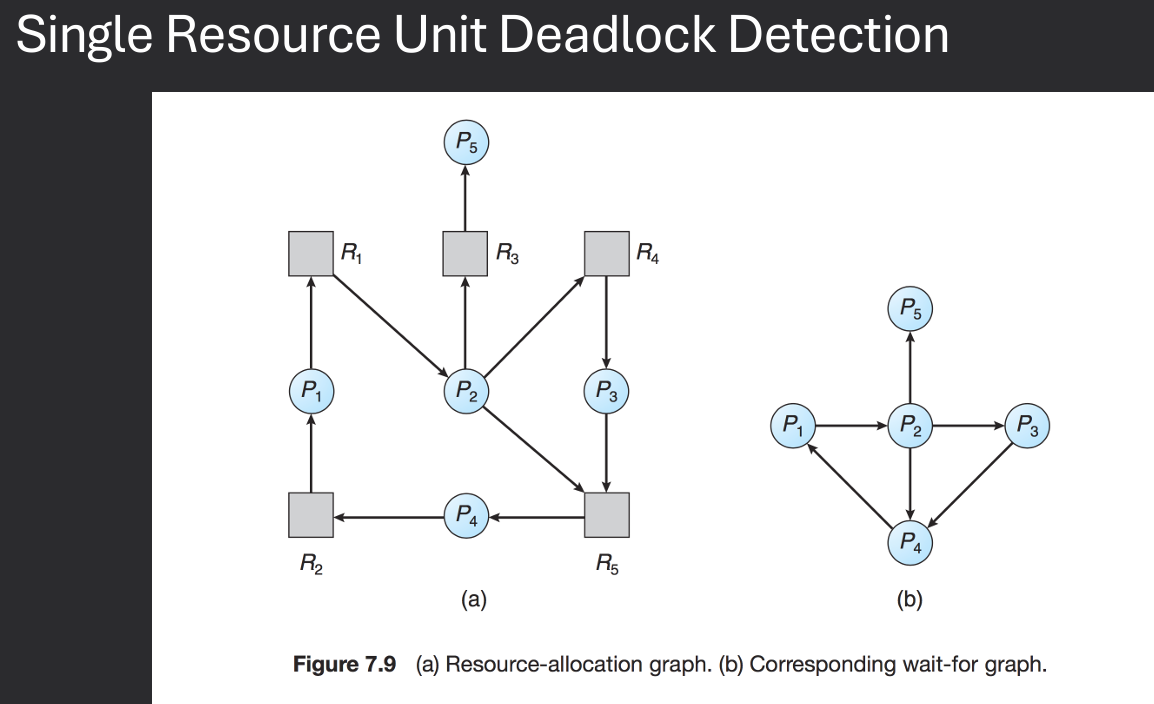

Easier for single resouce unit case, cycke → sufficient for deadlock.

To detect deadlock in the single unit case, collapse resource allocation graph into a wait-for graph and search for cycle.

An algorithm to detect a cycle in a graph requires an O(N^2) - order of N^2 operations. where N is the number of bertices in the graph.

Cycle detection is not applicable to systems with multiple-unit resources. Why? Deadlock needs a cycle, and cycle leads to deadlock if all resources single unit. Recall - circular wait is a necessary but not sufficient for deadlock.

Detection algorithm may need to brute force, attempting to reduce the RAG by checking all possible ways of allocating resources. O(n^2m) algorithm → n = number of processes, m = number of resources. If there is no way to allocate units to allow each porcess to finsih, them deadlock occurs.

How often should the deadlock detection algorithm be executed? Depends: How often is deadlock likely to occur? How many processes will be affected? Will anything terrible happen before a huamn being notices something strange? How much overhead can be afforded?